Takesada Matsutani, in Praise of Shadows

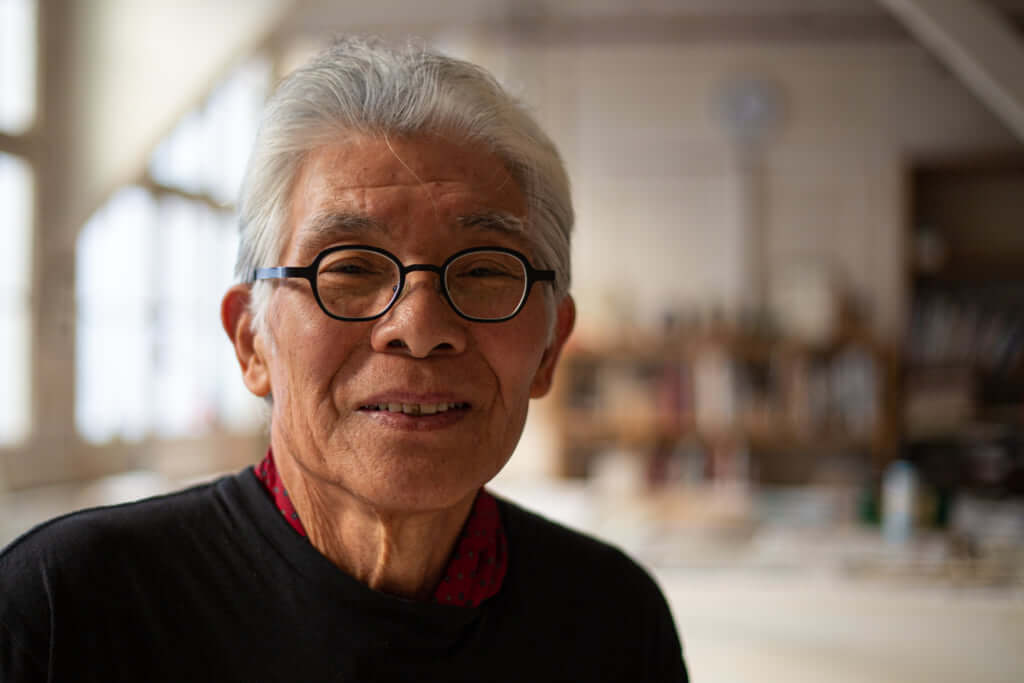

©Clémence Leleu

Takesada Matsutani is without doubt the most French of all contemporary Japanese artists. He moved to France in 1966 and set up a workshop in a courtyard in Paris’s 11th arrondissement, which is where he receives us. With round glasses perched on his nose and a fine red scarf around his neck, the 82-year-old artist tells his story in a mix of French and English, tinged with a Japanese accent. This blend of cultures is probably the central point for anyone wishing to form an outline of this artist who has been producing work uninterrupted for over fifty years.

But let’s start at the very beginning and go back to Japan, where Matsutani’s artistic career began. Aged 15, he fell ill with tuberculosis and was confined to his bed and a life of inactivity for several years. So, Matsutani started drawing everything that was in his field of vision: a cat, a dog, birds, and he even grew plants so he could document their growth on paper. His first work was therefore relatively realist, something that would change when he read the works of Russian artist Kandinsky, particularly Point and Line to Plane. ‘I realised that art was not only figurative. I therefore started to observe the knots in the wood on the ceiling of my room, and then drew those’.

©Clémence Leleu

The urgent need to create

This was in the 1950s, in a Japan still marked by the effects of the Second World War and the American bombing. ‘The United States destroyed the country but they didn’t destroy our spirit. So I decided to become an artist’, Matsutani explains. A self-taught artist who had to take classes from a distance due to his illness, the young man discovered Gutai, a Japanese avant-garde artistic movement that was born in the Kansai region and in which experimentation with materials and novelty were the key. ‘Jiro Yoshihara (the founder and theorist of the group – Ed.) wanted to create something new. After the war, Japan had borrowed a lot of things from Europe, so it needed to create something new, and not copy. I was heavily influenced by the group and wanted to be part of it’.

This wish was granted in 1963, when Jiro Yoshihara welcomed him to the Gutai group and he became one of its youngest members. He would go on to exhibit multiple works under its banner until the movement dissolved in 1972. ‘Gutai was an avant-garde group which was initially poorly understood in Japan. For Tokyo residents, Osaka seemed like the other side of the world. And there is a particular spirit in Osaka, which is very unlike the more conventional spirit of Tokyo’, explains Valérie Douniaux. This art historian and author of a thesis on Japanese artists in France from 1945 is now responsible for the artist’s archives. ‘But even in Osaka, Gutai was sometimes summed up as eccentrics creating installations’. The artists exhibited their work outside of galleries, occupying public space in stations or on the beach, and even in school playgrounds.

©Clémence Leleu

Vinyl glue: the inescapable element

Very soon, Takesada Matsutani found his preferred material: vinyl glue. ‘I just discovered by chance that it was possible to make shapes with glue. I’d put some glue on a canvas and then a gust of wind created what looked like stalactites. I liked the result so I decided to experiment with it’, Matsutani reveals. His work was exhibited at the end of summer this year at the Centre Pompidou, as part of the first retrospective dedicated to his work in France.

In his workshop, hairdryers and fans can be found alongside still blank canvases and pots of wood glue. This explosive mixture is now one of the artist’s trademarks, and he controls the material by blowing through a straw to make the glue inflate, before speeding up the drying process using fans and hairdryers. He then bursts the bubble, which gives his creations an organic, sensual quality. ‘I like this type of representation. At the time, this very organic and sensual interior image was what made me original’, the artist explains.

©Clémence Leleu

Matsutani and Paris

A competition would then change the course of Takesada’s life. In 1966, he was awarded the Franco-Japanese Institute prize and given the opportunity to travel to France for six months. 53 years later, Matsutani is still there. He remembers the culture shock he felt in his first few days in Paris. ‘There were very few Japanese people in France. And I didn’t speak a word of French. But I felt a great sense of freedom which you can’t feel elsewhere. I was given a space to work. I was respected just as much as my work was’, he remembers, before recalling how he left on a tour of Europe which led him in the footsteps of western art from Paris to Athens before landing in Cairo. This trip then took him back to the capital where he would settle for good, but regularly taking trips back to his country of birth.

In Paris, he met British painter and engraver Stanley William Hayter, and joined him in his Atelier 17 in Montparnasse. Matsutani dedicated himself to engraving and silkscreen printing, and it was there that he met his future wife Kate Van Houten. It was now the end of the 1960s, during the artist’s Hard Edge period in which bright colours appeared on the canvas. ‘Matsutani was heavily inspired by Ellsworth Kelly, an American abstract artist, but maintained his attraction to organic shapes, which he mixed with rectangles’, explains Valérie Douniaux.

©Clémence Leleu

A return to black and white

This period concluded at the end of the 1970s, when the artist returned to black and white and, in short, to his Japanese culture, so appreciative of this pair of colours. ‘I wanted to do something new’, explains Matsutani. ‘I can’t write novels or poetry, so I drew a series of lines in pencil. Someone saw my work and said “That’s great, you should do it bigger”. So I bought some Canson paper and drew 80 cm-long lines every day, like a diary’.

Vinyl glue also made its return, the bubbles adding relief, something so dear to the artist, and particularly creating areas of shadow in a subtle homage to Junichiro Tanizaki, author of In Praise of Shadows, a novel which the artist read soon after creating his last canvases. ‘Settling in France allowed me to discover my Japanese culture’, the artist reveals. ‘I’m not 100% European, and I always wonder what to do with my Japanese culture. But I’m not nostalgic; I keep hold of this Japanese side. I take the best of both cultures, while continuing to do something nobody else does’.

Matsutani therefore remains loyal to the philosophy of Gutai, which took on a new dimension as the artist returned to his performance-based, monumental beginnings with the creation of Stream, this series of strips of paper darkened with graphite, but 10 metres long this time, the ends of which the artist showered with turpentine to blur the lines.

As the interview concludes and we ask Matsutani how he would sum up the body of work he has produced up to now, being as vast and prolific as it is, he responds with a mischievous smile: ‘I would say that it’s not enough. It’s not finished yet!’

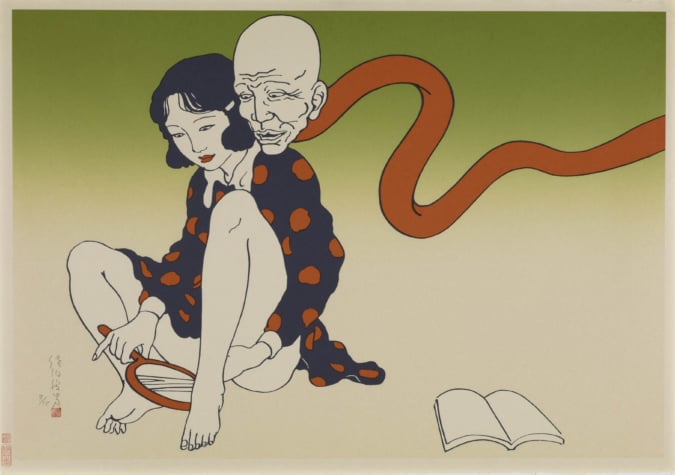

Photo ©Kaoru Minamino. ©Takesada Matsutani. Courtesy de l'artiste et Hauser & Wirth

Courtesy de l'artiste et Hauser & Wirth. Photo © Marc Domage

©Takesada Matsutani. Courtesy de l'artiste et Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Patrick Rimond

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.