Adam Norgaard, Painting Cultural Differences

Living in Japan, the American artist patiently works to represent a culture that shakes him up in all senses of the term.

Adam Norgaard, ‘Bonsai Inspector’ (2021)

Adam Norgaard is undeniably sensitive to the work of major names in Japanese art, who he cites freely. However, the shock of discovering the difference in mentality and culture between his country of origin, the United States, and that where he lives today has more of an influence on his work than these references.

Having been attracted to Japanese culture and intrigued by the complexity of the language from an early age, Adam Norgaard decided to study Japanese at college, then settled in Kawasaki from his third year. When he returned to the United States, where he trained at the Academy of Art University – School of Fine Art in San Francisco, then in Portland, he decided to settle in Japan definitively, keen to maintain his mastery of Japanese.

The artist, born in 1991, is primarily fascinated by the Japanese mentality, particularly the way of approaching life in society, uchi-soto. As he explains to Pen, ‘Japan is extremely homogeneous and people are divided into two groups, the uchi (insiders) and soto (outsiders). When painting a figure I often depict them as being othered, largely based on my experience at attempting to assimilate to life here as an outsider’.

Obliged to observe and persevere

He discovered artistic creation through literature and cinema in particular: Yoshitomo Nara on the cover of the book Hardboiled & Hard Luck by Banana Yoshimoto and costumer and designer Eiko Ishioka via her collaboration on the film Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters by Paul Schrader. Adam Norgaard’s paintings transcribe with finesse — in the use of colours, contrasts and different planes — his desire to infiltrate, decode and integrate as much as possible in his new environment.

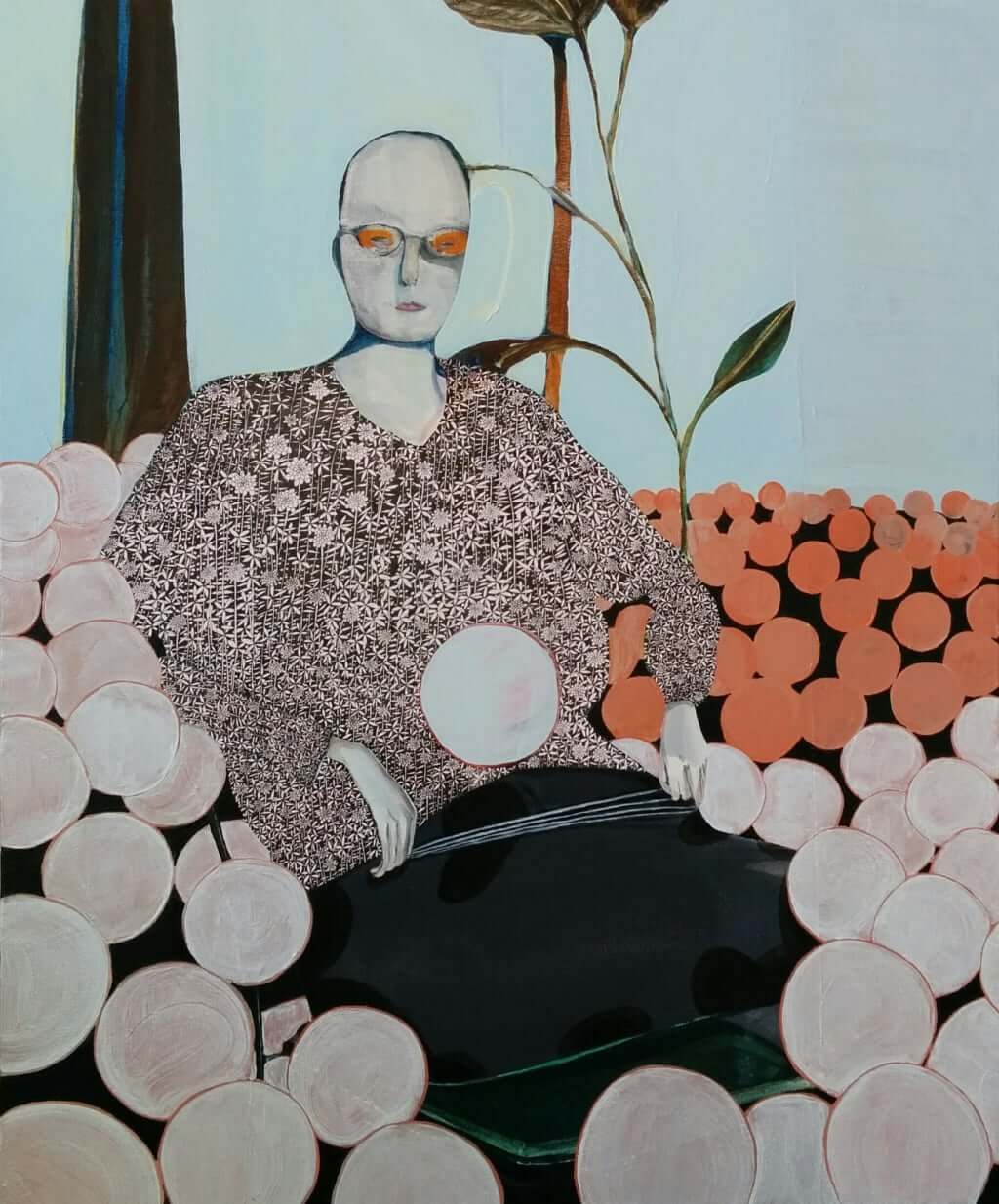

Each piece is born out of a moment, an observation of the environment in which he has been immersed since 2014. In 2015, then, he produced White Thread. This piece arose from a memory, that of a journey on the metro, during which he observed those around him, ‘a mass of homogeneous commuters. Coming from a diverse country it was an extraordinary thing’, declares Adam Norgaard. In White Thread, the character depicted ‘is surrounded by orbs of two different hues. The white orbs seem to congregate around the figure… A plant rooted in the orange group attaches itself to the figure. This suggests that the figure is not in the correct environment needed to thrive’, the artist continues.

Different forms of expression

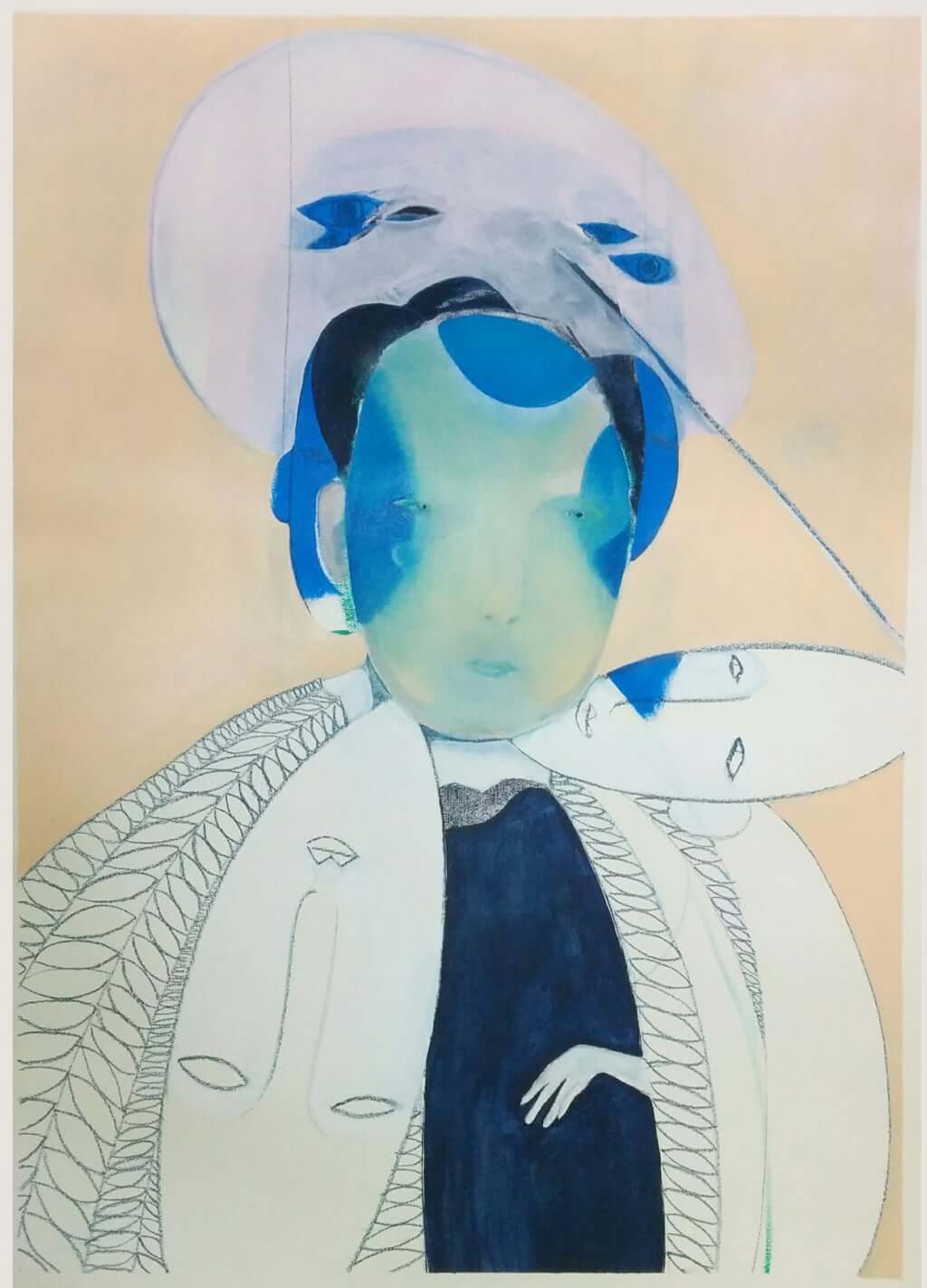

Another example can be seen in Encounter 1 (2016). This painting addresses a major reference in Japanese culture, noh masks. Adam Norgaard explains how he heard that they ‘appear to change their expressions depending on the angle that they’re tilted’. When the masks are tilted upwards, they appear to be smiling, and when tilted downwards, they ‘frown… I depicted several different masks in this painting. The mysterious thing about this painting is that the viewer doesn’t know if the central figure is wearing a mask or not’.

His more recent work focuses on a symbol of Japan, bonsai, a botanical art at which he failed. In Bonsai Inspector (2021), a bonsai master is shown at work, surrounded by his assistants.

Adam Norgaard’s work is the fruit of adaptation to a cultural and social environment that is more restricted than the one in which he was born, and a form of resilience. ‘Working in Japan takes a lot of patience. Some people call it a culture of gaman (a Zen Buddhist term for perseverance). There are size constraints and also social constraints. For westerners I think the biggest culture shock is the collectivistic culture’, which particularly leads to stronger restraint in the expression of one’s feelings ‘for the sake of what the group in its entirety might think’, declares the artist.

The artist’s work can be found on his website.

Adam Norgaard, ‘Encounter 1’ (2016)

Adam Norgaard, ‘White Thread’ (2015)

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

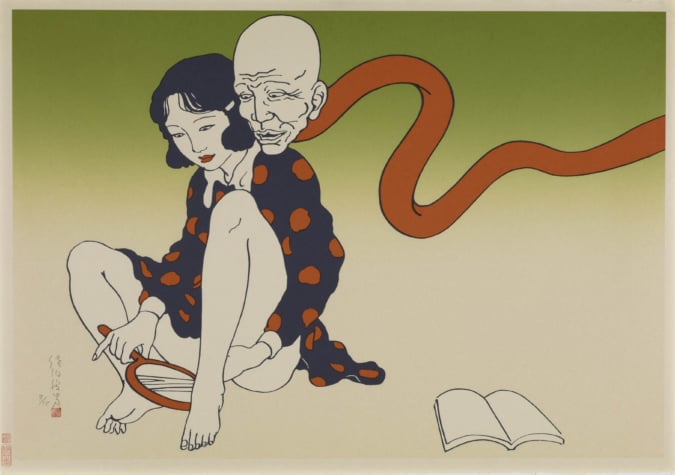

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.