Twenty Years of Nicolai Bergmann’s Flower Box

©Robert Kirsch

From the torii of Fukuoka’s Daizaifu Tenmangu Shrine, to the steps of Kyoto’s Kiyomizu Temple, and the construction sites of Tokyo, Nicolai Bergmann has been decorating the streets of Japan with his flower designs for the past two decades. In the lead-up to the twentieth anniversary celebrations of the design that kick-started his career – the innovative ‘flower box’ – we spoke to Mr. Bergmann about his early dreams of becoming a florist, and some of the more unusual ventures he has undertaken.

As a child in Copenhagen, Nicolai Bergmann was surrounded by nature, from the apple plantations of his grandparents, to his father’s plant business and the farms worked by his relatives. Other than a brief interlude intending to follow in the footsteps of his farming relatives – a career that ultimately held too little excitement for him – Bergmann’s dream has never wavered: to have his own flower shop. Journeying across the world as a teenager with his father’s plant business, Bergmann first stepped foot on Japanese soil at the age of 19. Although initially awed by the sheer size of the Japanese skyline, it wasn’t until he returned home to the comparatively low-lying Denmark that he realised the potential and energy Japan has to offer. It only took nine months before Bergmann was travelling back to the land of the rising sun.

©Robert Kirsch

Success in Japan came to Bergmann in a rather roundabout fashion. Two decades ago, when he had just opened his first shop, a customer came to Bergmann with an ambitious and intriguing commission: produce 600 flower-gifts for an event, but all 600 must fit on a single tabletop. The budget was limited and the space even more so. Not one to shy away from a challenge, Bergmann began experimenting with designs until he came up with the idea of lidded boxes, allowing the flowers to be neatly stacked. Excited with his new design, he made numerous samples, only to be told that the customer had found something else. Disappointing though this was, the flower boxes, defiantly displayed in the store where Bergmann was working, began to draw a lot of interest. ‘What is that? How do you use it?’ It was these kinds of questions that caught Bergmann’s attention and hinted at just how popular the flower box might become. The flower box caught the attention of the buyers of the select shop ‘ESTNATION’, and made such an impression that the first ESTNATION store opened under the brand name ‘Nicolai Bergmann Flowers & Design’. Today, the flower box has more than 1.5 million hashtags on Instagram.

Bergmann describes the DNA of his style as a fusion between Denmark and Japan. While his entire career has been based in Japan, he admires the ‘clean lines’ of Denmark, and lists Danish architect Arne Jacobsen and furniture designer Carl Hansen as sources of inspiration. Bergmann also acknowledges that his position as a foreigner, in combination with his reputation, has earned him access where others may have been denied. A perfect example is his biennial exhibition at Daizaifu Tenmangu Shrine in Fukuoka. Over the course of several exhibitions, Bergmann had built such a relationship of trust with the priest of the shrine that when he asked for permission to wrap the shrine’s 50m torii entirely in pink, he received a reply in just one day. The priest at Tenmangu ‘has become like family’ to Bergmann, meeting him at the airport upon each visit. It is hard to imagine anyone else being met with such familiarity in this sacred place.

©Robert Kirsch

While always striving for another success like the flower box, Bergmann concedes that such a feat is rarely achieved twice. Instead, Bergmann is focusing his energy on large-scale projects. Currently under development is a flower park in Hakone, set to open in 2021. ‘It will be a very simple place, where you can just enjoy nature.’ Visitors can expect a chic park, almost four hectares in size, with pieces of land art Bergmann has made from natural materials. These objects will be sourced from various locations across Japan. Notably, Bergmann will be using stone from a project he completed in Fukushima, building a playground for children of a school harshly affected by the 3/11 earthquake, as well as trees and plants from the site of his new gallery in Omotesando. In effect, this will be a nationwide project, collected in one place.

In honour of the 20th anniversary of Bergmann’s flower box, three exhibitions, each spanning several days, will be held in various locations across the country. Starting with Tokyo’s Roppongi Hills in November, the celebrations will continue to Fukuoka’s Daizaifu Tenmangu Shrine and Kyoto’s Kiyomizu Temple next year. The exhibitions will include archives of Bergmann’s works, digital installations, collaborations with different artists, and of course, the flower box – visitors will even get the chance to make their own. Trying one’s hand at this delicate process may go some way toward demonstrating the difficulties Bergmann has faced, building his business up from scratch. But, as Bergmann himself affirms, if your vision is easy, it isn’t worth pursuing. ‘What I would really like to express is that if you have the drive and the creativity in whichever field you are in, there is no limit to the direction you can take it. I started as a florist, but I do so many other things now…there are endless opportunities if you put your mind into what you do.’

©Robert Kirsch

©Robert Kirsch

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

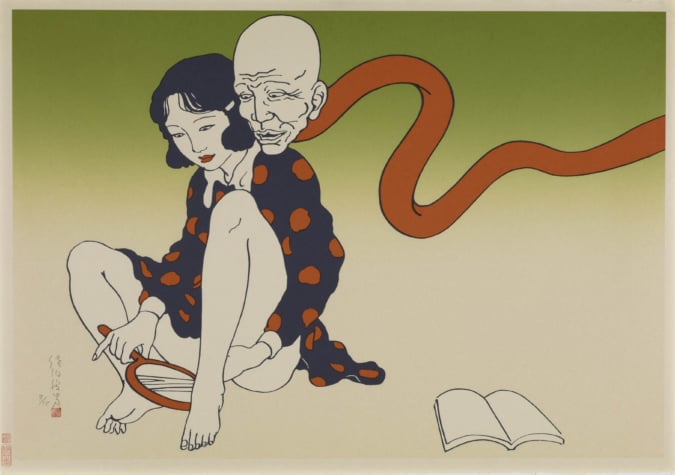

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.