Shojin Ryori, Japanese Buddhist Vegetarian Cuisine

©Atsushi Sano

One soup and three dishes made from seasonal vegetables, all locally sourced if possible, and all served with a bowl of rice. This is the principle of ‘ichiju sansai’, the type of traditional Japanese meal that has been made into a vegetarian version for shojin ryori. Literally translating to ‘devotion cuisine’, shojin ryori is closely linked to Buddhism and generally eaten in temples. It is characterised by its simplicity and refusal of waste.

Shojin ryori began to develop during the 18th century in Japan, in conjunction with the expansion of Zen Buddhism and monks such as Dogen. The latter played a large part in the codification of seated meditation, or zazen. Devotion cuisine needs to accompany the practice of meditation and promote the balance and alignment of the mind and body. It therefore contains fresh, light ingredients, but no meat, because killing animals clouds the mind and is contrary to the principles of Buddhism. The same goes for overly pronounced flavours which are forbidden, for example garlic and onion, and for root crops, as pulling these up is also not allowed.

The ingredients most commonly used in shojin ryori are therefore soy-based, for example all kinds of tofu (including goma-dofu, which is made from sesame), wild plants from the mountains, such as kuzu, and even roots. Meals often have to respect the rule of ‘five’. First, there must be five colours, with a preference for white, green, yellow, red and dark (black) ingredients. Then come the five flavours: sweet, bitter, salty, sour and ‘umami’, described as a savoury taste. Finally, the five methods of preparation must be adhered to, with one ingredient being raw, one stewed, one boiled, one roasted and one steamed. For those wishing to take this perfectionism even further, there is also the theory of the five elements, or godai.

Despite its many rules and its seeming simplicity, shojin ryori could not be any more tasty. It prioritises the natural flavour of ingredients, which it brings out without over-seasoning. How could anyone resist nasu dengaku, aubergines with caramelised miso, or a handful of deliciously crispy vegetable tempura? Everything about the preparation is designed to restrict the amount of waste. For example, vegetable and plant skins and stems are reused to flavour the stock, and the leaves can be used as a decoration. Everything has to be eaten! And in silence, as tradition dictates.

For those wishing to try shojin ryori, there’s nothing like a trip to Koyasan and its many temples which offer shukobo, or lodgings, and typical meals that form part of devotion cuisine. Or, take a trip to the mountains in Nagano where Zenko-ji, one of Japan’s oldest temples, can be found, and where ancient Buddhist traditions are preserved.

Visitors can get close to nature, just as the yamabushi, or mountain monks, did, following the shugendo doctrine. Their asceticism is intended to lead to spirituality, and is something that today’s society could learn a lot from.

©Atsushi Sano

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

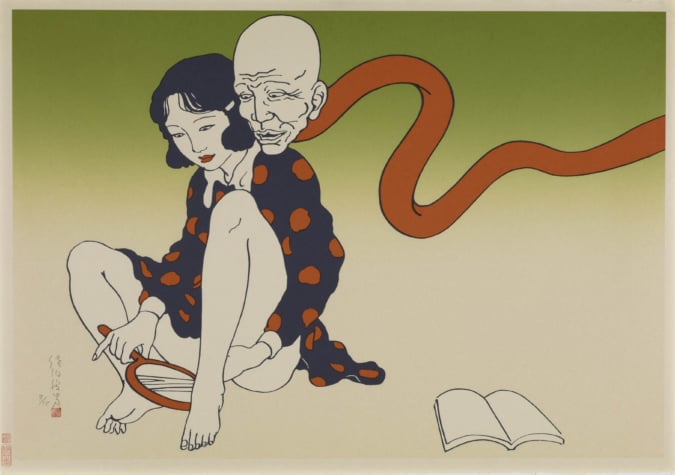

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.