Japan and the Bauhaus

Forced into exile by the Nazis, the instigators of the German school took refuge in Japan where they found concepts dear to their movement.

© Bauhaus Archiv Berlin

2019 marked the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus, the German school of art, architecture and design. This school, founded in Weimar, brought together the whole of the creative avant-garde both within and outside of Germany in just fifteen years of existence. Its ambition? To unite art and technical design and invent a new way of inhabiting spaces.

Forced into closure by the Nazis, the Bauhaus school nevertheless continued to develop over the years, so much so that branches of it can still be found today, all over the world, from the USA, where a number of the grand masters of the movement went into exile, to Europe and Japan.

In Japan, particularly in the domains of architecture and craftsmanship, the key figures of the Bauhaus found notions dear to the movement such as minimalism, functionalism, and the use of raw materials.

Marked similarities

‘I was surprised to discover how certain attitudes and ways of approaching things in Japan were similar to certain basic convictions held by the Bauhaus, which I founded in 1919 in Germany’, explains Walter Gropius in his book The Japanese House – A Tradition for Contemporary Architecture, following his first trip to Japan in 1954. ‘In Japanese houses, the spiritual links between man and his residence have been made visible thanks to a humanised approach that links the two needs, mental and emotional, of man. The spiritual and practical demands of life have been coordinated in an artistic manner, which represents one of the most precious contributions to a universal philosophy of architecture.’

The way in which Japanese architects and artisans envisage space, particularly their relationship to emptiness and fullness, also interested the members of the Bauhaus. Obsessed by the flexibility and modularity of spaces, and by the asceticism that should prevail in interiors, Walter Gropius and his associates saw the Katsura Imperial Villa, east of Kyoto, as a modern architectural gem. ‘One of the positive points of old Japanese construction is the flexibility of the space. The house opens onto the garden and is connected to it. The interior and the shoji create what I call modern coordination. This ‘ready-made’ construction is very important. The simple beauty of the Katsura Imperial Villa is certainly the peak of beauty’, enthuses Walter Gropius who, alongside his Japanese counterpart Kenzo Tange, dedicated a work to this edifice.

Japan as a source of inspiration

However, long before Walter Gropius’s visit to Japan, the country had already inspired some of the school’s professors. One of these was Johannes Itten, a painter whose lessons notably concerned the aesthetic of Japanese ink painting and who initiated his students into Buddhist and Shintoist philosophy, so dear to the Japanese.

One of his students, Theodor Bogler, took inspiration from Japanese tradition when creating his series of teapots that combined modularity and geometry, two concepts upheld by both the German movement and Japanese art. In the same vein, Marianne Brandt designed a tea infuser made from brass and ebony in the shape of a half-sphere, where the cultural mix of east and west gave rise to one of the most iconic pieces of the Bauhaus movement.

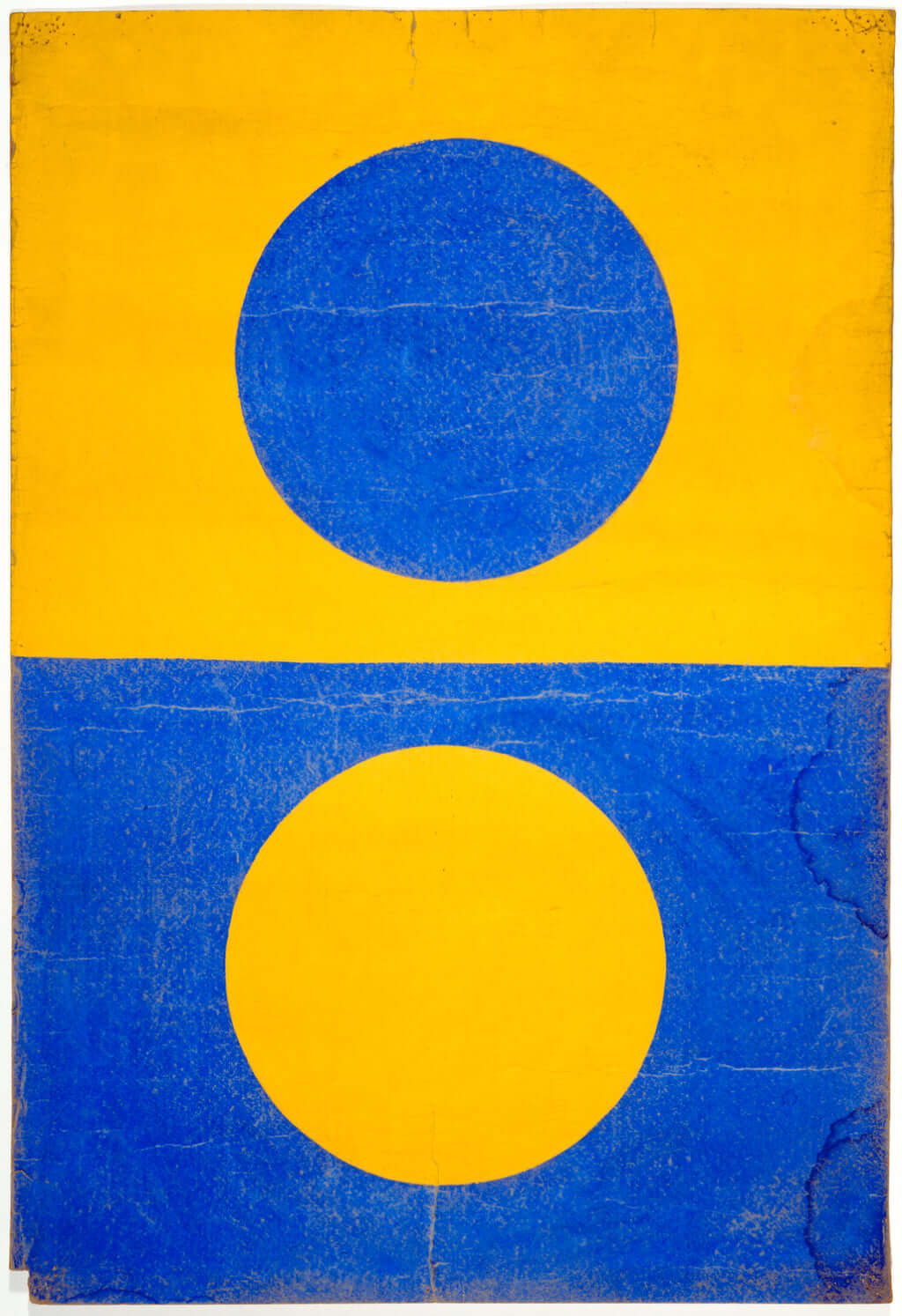

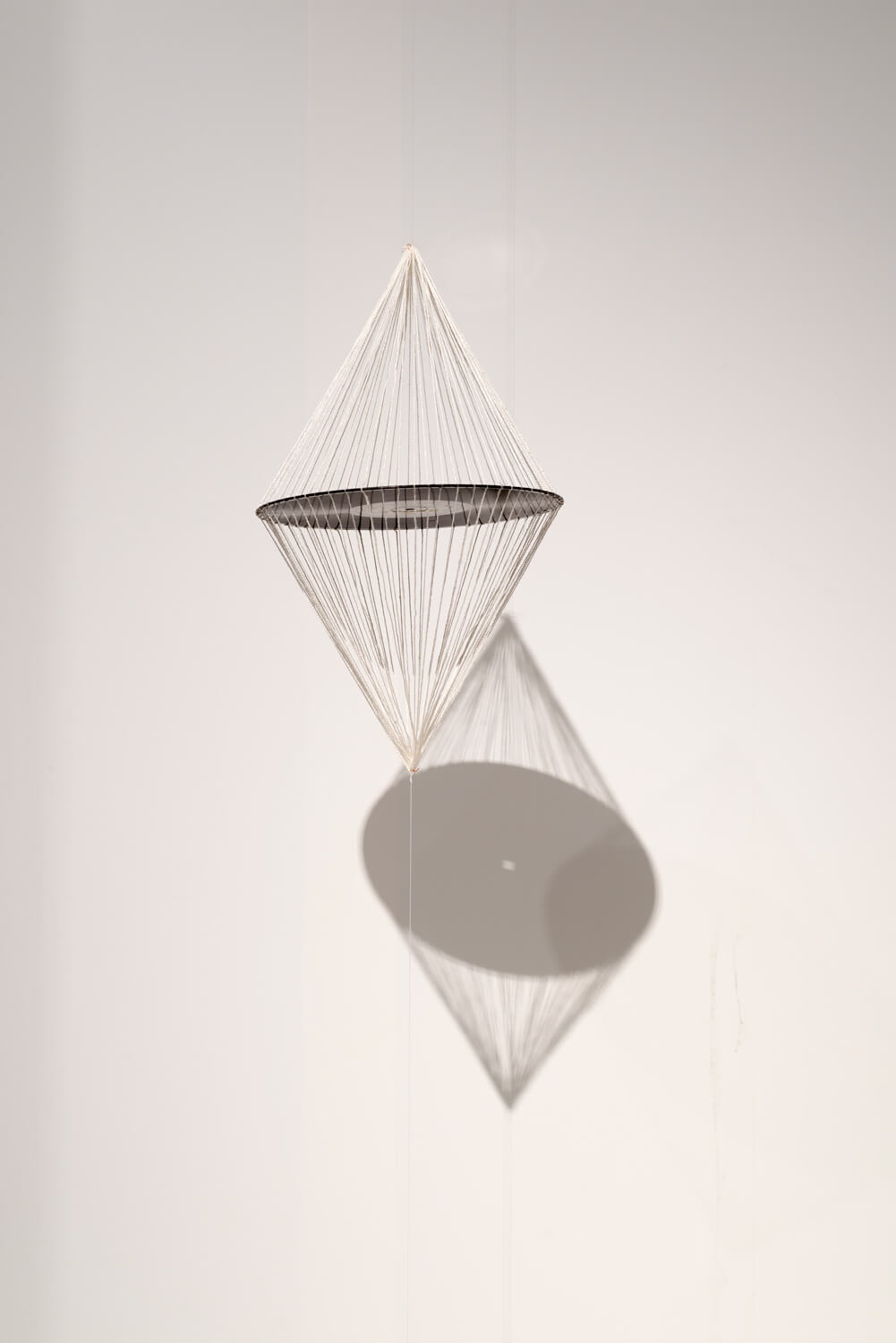

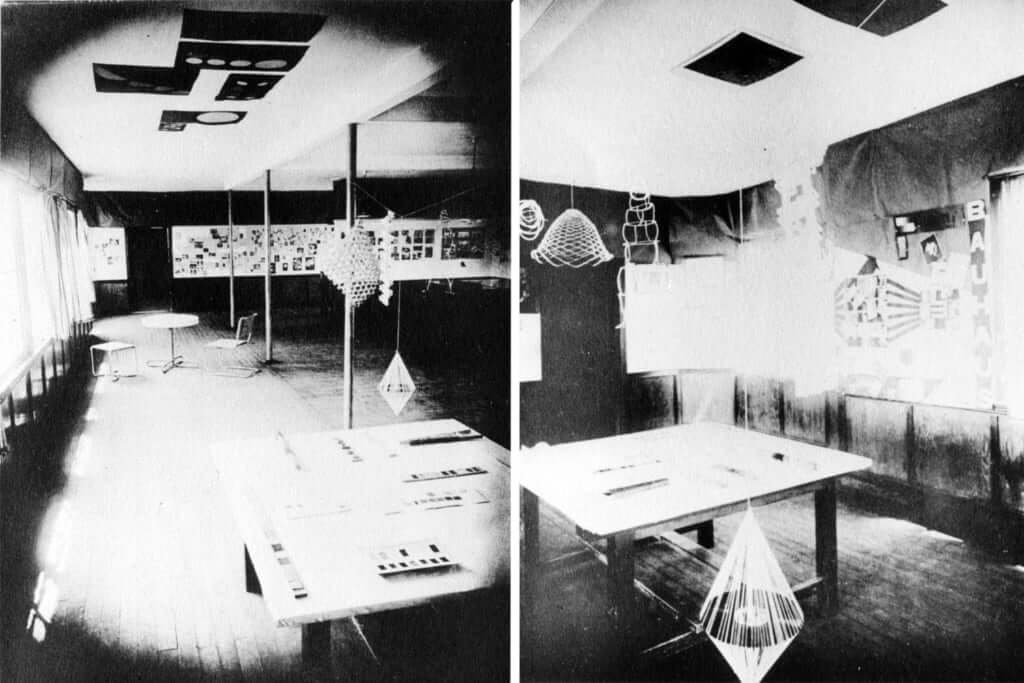

Japan eventually made its presence known on German soil when two Japanese students, Iwao Yamawaki and Takehiko Mizutani, joined the famous school. The latter was the first Japanese student of the Bauhaus, having joined in 1927, and his works quickly gained success, like his round glass table project. When he returned to Japan, he organised the Exhibition of Life Construction, which showcased the ideal aesthetic of the Bauhaus. This exhibition was considered as the prelude to the new school of architecture and design, whose teachings combined the concepts of traditional Japanese design and the European modernism of the Bauhaus with industrial production.

More information on the Bauhaus can be found on a dedicated archives website.

© Bauhaus Archiv / Fotostudio Bartsch

© Bauhaus Archiv / Foto: Gunter Lepkowski

© Bauhaus Archive

© Kenchiku Gaho / October issue, 1931. Photographer unknown

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

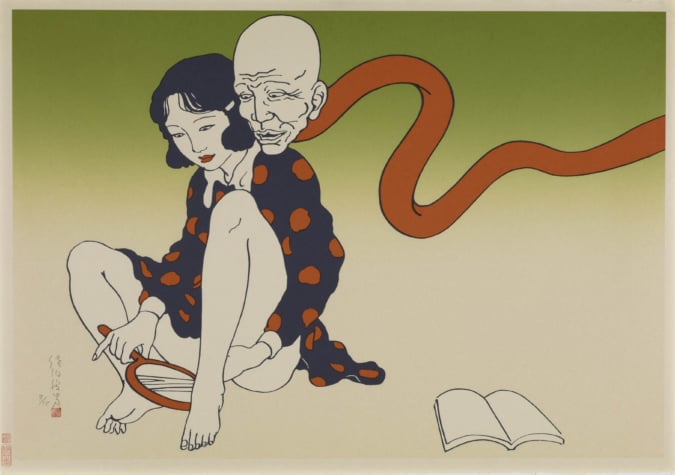

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.