‘Ekiben’, the Art of Lunchboxes for Train Journeys

These delicate bento often contain culinary specialities from the town or prefecture where they were purchased.

© NOBU

In Japan, train journeys are far more than simply a means of getting from one place to another. People admire the landscape that runs past the window, the countryside and traditional houses quickly overtaking the buildings and other structures found in the megalopolises. They also witness the procession of Japanese travellers who have gone to visit another city for the day or weekend. But these train journeys, lasting several hours, are also an excellent way to sample an integral part of Japanese culture: ekiben, formed from the words eki uri bento, or ‘boxed meal sold at the station.’

Discover Japanese culinary specialities

Although it is very poorly looked upon in Japan to eat a snack on the underground or on the smaller train lines where journeys only last a few minutes, people are allowed, and even advised, to eat an ekiben on longer train journeys. However, it isn’t a meal to be taken lightly. There are no sandwiches made from sliced bread or instant noodles; ekiben are delicate bento often containing culinary specialities from the town or prefecture in which travellers begin their journey.

Prepared that morning from fresh products, they generally contain rice or noodles, accompanied by seasonable vegetables and some meat or fish. The contents are packaged in a wooden or plastic box, or even a ceramic pot, a speciality in Hyogo Prefecture (grouping the cities and surrounding areas of Kobe, Himeji, and Nishinomiya). Ekiben are most often served cold, but for a few years now, some prefectures have been offering options that are served hot, like Miyagi Prefecture with its Tan To bento. You pull on a string, which sets off a chemical reaction in a little pocket found under the dish and it reheats it in just five minutes.

A culinary tradition dating back to the 19th century

These boxed meals, which have been delighting Japanese travellers’ taste buds since the end of the 19th century, when the country’s first railways were built, are continually being reinvented by such innovations as the above-mentioned reheating technique, with typically Japanese charm. In those early days, ekiben sellers rushed around on station platforms, their arms piled high with heavy wooden boxes, trying to sell meals to the first rail passengers. With each new line that opened, another ekiben was born.

The selling technique is slightly more organised now, with kiosks specialising in these gourmet boxes installed directly on the platform in the stations with the most popular train lines. There is even an establishment on the first floor of Tokyo Station, named Ekibenya Matsuri, which offers over 170 kinds of ekiben for those wishing to taste delicacies from prefectures they might not have the opportunity to visit. It’s a different form of travel.

To get a better idea of what ekiben look like, more information can be found on the Ekibenya Matsuri website (only in Japanese).

© JNTO

© JNTO

© NOBU

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

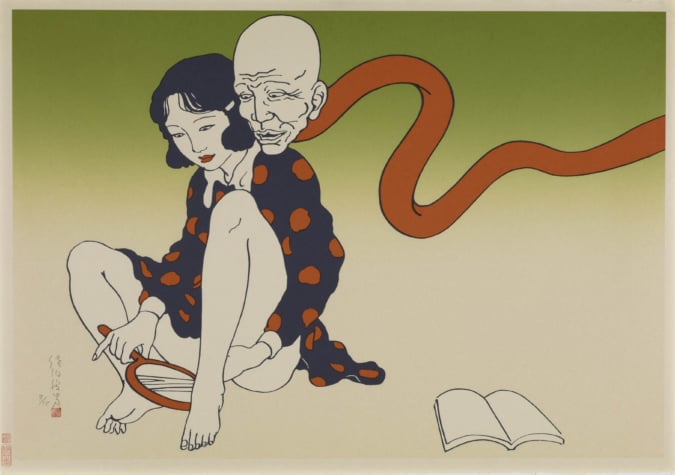

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.