Mono-ha, or the Disappearance of the Sun

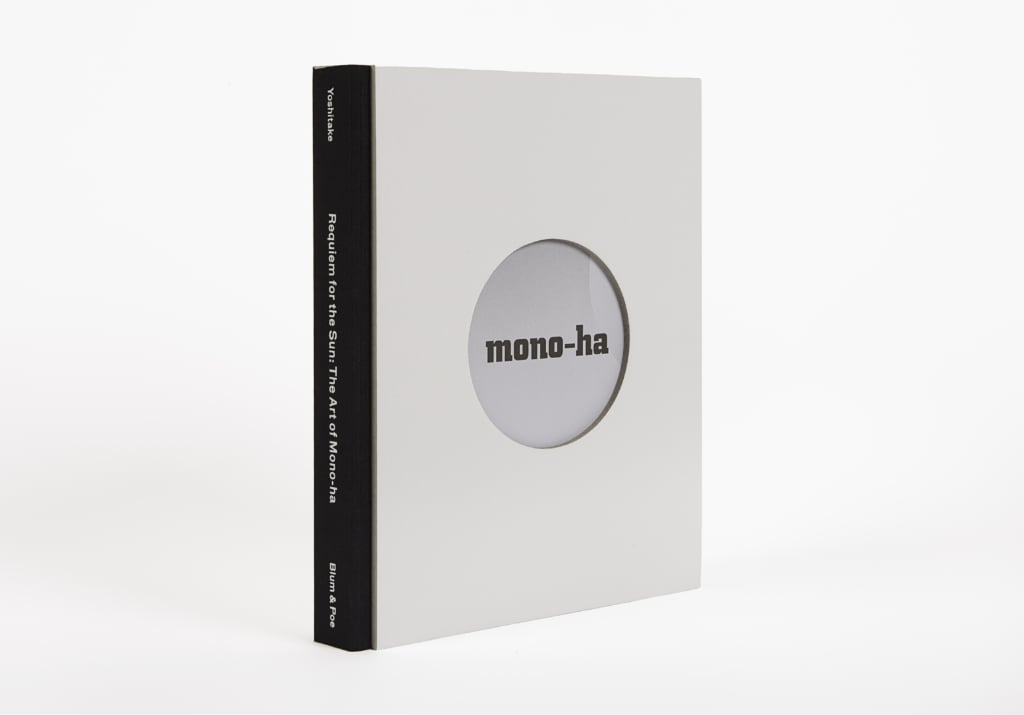

Mika Yoshitake's book 'Requiem for the Sun' retraces the birth of a group of artists linked to the beginnings of contemporary Japanese art.

“Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha” - Curated by Mika Yoshitake, Installation view, 2012 - Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Photo: Joshua White Courtesy of the artists or Estates and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo

Mono-ha literally translates as ‘school of things.’ It was based around this term that a group of Japanese artists sought, beginning in 1968, to relearn ‘to see the world as it is, without subjecting it to an act of representation that opposes it to man.’ The movement brought together Nobuo Sekine, Lee Ufan, Kishio Suga, Katsuro Yoshida, Katsuhiko Narita, Shingo Honda, and Susumu Koshimizu. Published in 2012 by the Blum & Poe gallery—on the occasion of an exhibition—the book Requiem for the Sun by curator Mika Yoshitake allows readers to understand the specificities and importance of the group’s approach.

Requiem for the Sun focuses particularly on the group’s activity in Tokyo between 1968 and 1972 (the end of the movement is generally dated as 1975), in a period marked by political upheaval in Japan. It raised its voice against the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan (1960), the Vietnam War, and the petrol crisis, taking a critical look at the industrialisation of the country.

Materials, space, and the viewer

The title of the exhibition and book refers to the symbolism of the sun, which is very present in the Japanese aesthetic, and which faded away during the post-war period in favour of artistic detachment and a new regard for material. The artists aimed to scale down their intervention to pay closer attention to the relationship between materials, space, and the viewer.

Like Arte Povera in Italy—which also aimed to make insignificant objects significant and attached greater importance to the process than the final creation—the artists in the Mono-ha movement did not, strictly speaking, constitute a group; their processes were in parallel and they worked alone, in an uncoordinated manner. They shared a desire to bring natural and industrial objects face to face: steel, stone, wood, glass, or Japanese paper. This wish to create a dialogue between natural and manufactured objects is demonstrated in the pieces showcased here. Phase – Mother Earth by Sekine Nobuo—exhibited for the first time in October 1968 in Suma Rikyu Park in Kobe—is a large cylinder made from earth and concrete, positioned right next to the hole from which it was dug. The piece is considered as the origin of Mono-ha. Meanwhile, Lee Ufan used rope to tie planks of wood around a pillar, and Koshimizu Susumu cut a block of stone for Splitting a Stone–February 25, 2012, 2:40pm.

As Mika Yoshitake notes in the book (written with James Jack and Oshrat Dotan), ‘Mono-ha was ultimately a rejection of the Euro-American avant-garde and is now synonymous with the beginnings of contemporary art in Japan.’ Although the movement was limited to just a few years of artistic activity in Japan, it opened up the path to over half a century of creation.

Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha (2012), a collection by Mika Yoshitake, James Jack, and Oshrat Dotan, is published by Blum & Poe.

“Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha” - Curated by Mika Yoshitake, Installation view, 2012 - Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Photo: Joshua White Courtesy of the artists or Estates and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo

“Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha” - Curated by Mika Yoshitake, Installation view, 2012 - Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Photo: Joshua White Courtesy of the artists or Estates and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo

“Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha” - Curated by Mika Yoshitake, Installation view, 2012 - Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Photo: Joshua White Courtesy of the artists or Estates and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo

“Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha” - Curated by Mika Yoshitake, Installation view, 2012 - Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Photo: Joshua White Courtesy of the artists or Estates and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

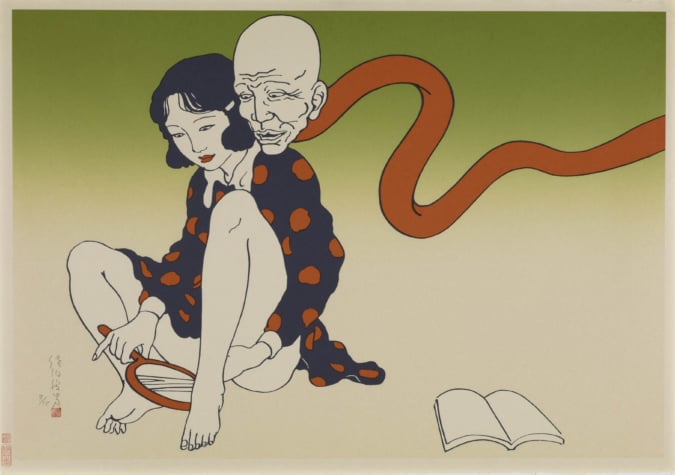

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.