Susumu Shingu: An Ode to Nature

Sculptor, mechanical engineer, and architect of a utopian village, the artist boasts a protean body of work based around nature.

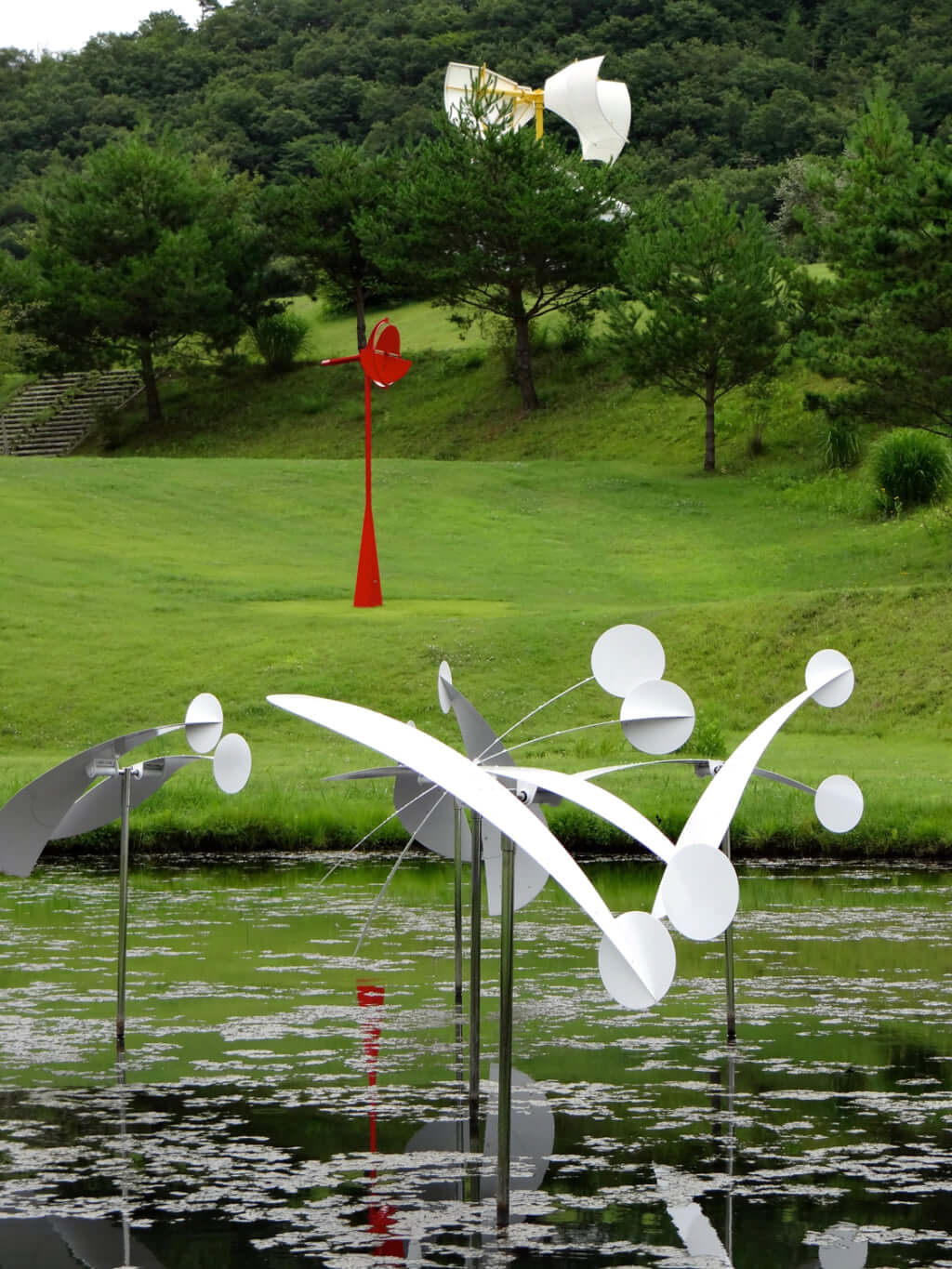

Wind Museum Susumu Shingu (Sanda, Japan) 2014 © Jeanne Bucher Jaeger

The works of Japanese artist Susumu Shingu border on meditation. When looking at his installations, some parts of which come to life thanks to the force of the wind in a perpetual movement, but one which has been cleverly orchestrated by the creator, time seems to stand still. The viewer is therefore immersed in a sort of bubble, in which the only things that matter are nature and movement.

‘My works are ways of translating the messages of nature into visible movements’, explains Susumu Shingu in an interview with Pen. ‘What I try to show is the beauty of our planet and how lucky we are to be born here as human beings. For me, there are no boundaries between art, mechanics, science, and the production of picture books and artistic practice.’

Natural elements used as materials

The artist’s playground is the outdoors. He uses parks, gardens and areas around rivers or ponds to install his moving sculptures, created from high-tech materials and using innovative technology, the movements of which Susumu Shingu regulates in fine detail. However, beyond the materials used to create his moving sculptures, the artist seeks to harness the natural forces of water, wind, waves, energy, and gravity, as if to breathe a life force into them to make them mobile.

‘It’s not just beautiful, it’s scientifically adjusted’, explains Bernard Vasseur, Director of the Centre de recherche et de création Elsa Triolet – Louis Aragon and author of Shingu, a book presenting the work of the Japanese artist, of whom he is now a close friend. While people might seem surprised by the artist’s use of non-natural materials to create his sculptures, he sweeps this aside. ‘It has to be solid. Susumu Shingu does not create land art, he does not take elements from the landscape to produce his works. His work is exposed to the outdoors, to the wind. And in Japan, wind can take the form of a typhoon.’

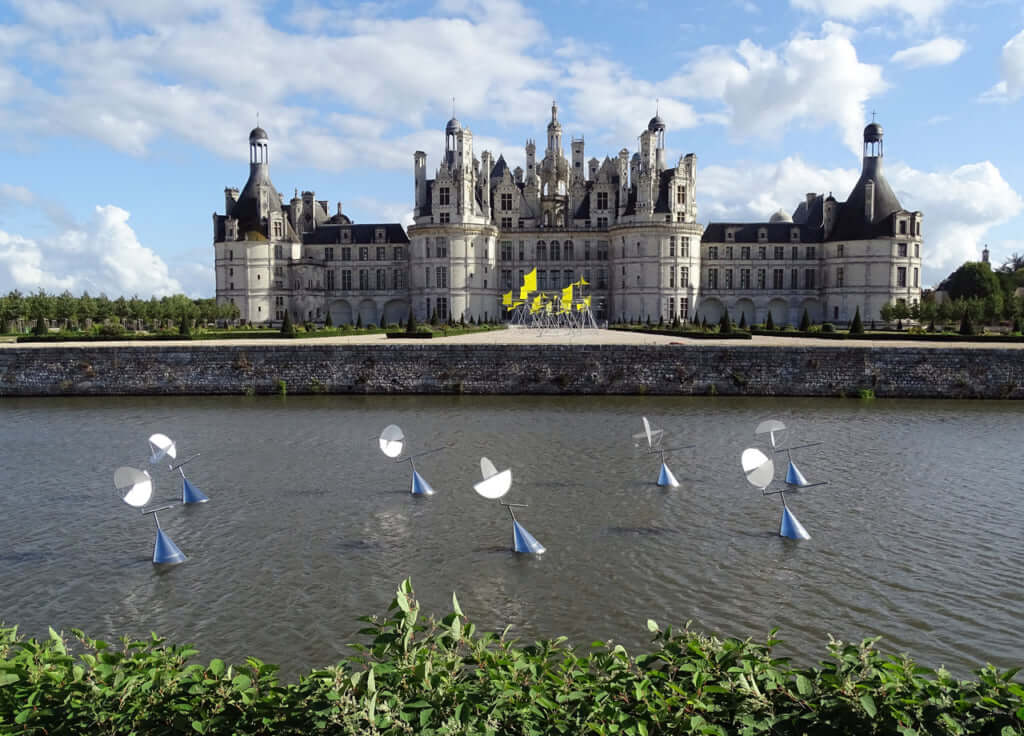

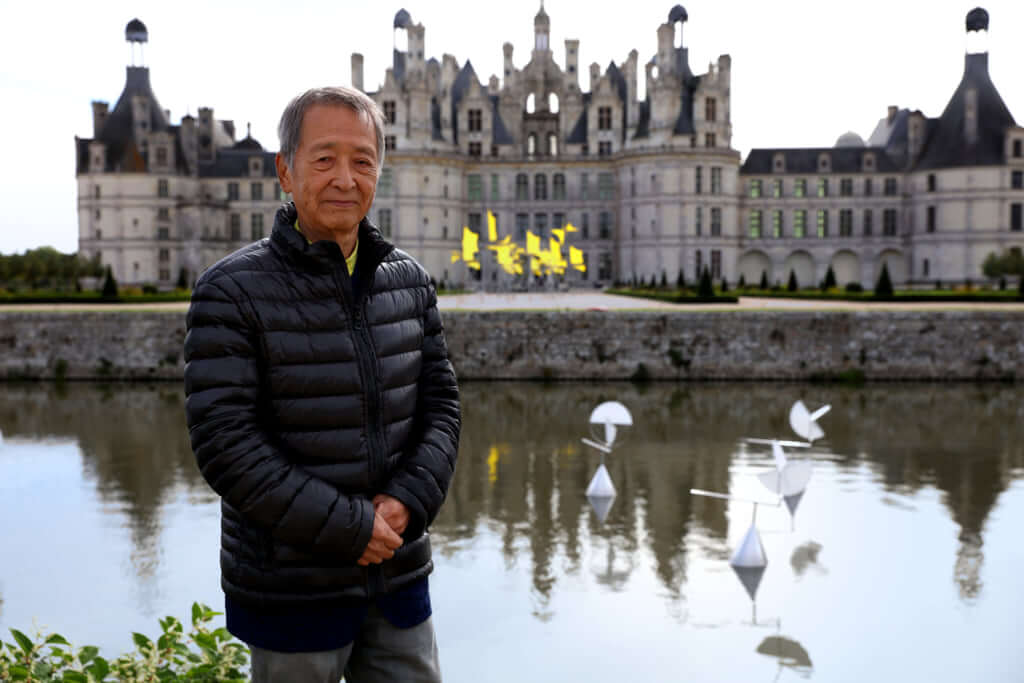

As well as being exposed to the four winds, Susumu Shingu’s work travels across the world, like Wind Caravan, an installation of mobiles that has passed from Japan to New Zealand via Finland and even Mongolia. This is a good way to test the structures, and also to gauge how his work is received by diverse cultures. One of the stops was at the Château de Chambord, where the artist’s work was exhibited from 2019 until 2020.

An Italian connection

This stopover at Chambord is of particular importance to the artist. His exhibition, Susumu Shingu: A Utopia for Today, came a few months after another, entitled Chambord, 1519-2019: Building Utopia, which featured the work of Leonardo da Vinci, among others. ‘2019 was the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci. It was a bit like Leonardo had called me himself to participate in the exhibition’, explains Susumu Shingu. Because, as with nature, the artist has close links with Leonardo da Vinci.

‘When I look back, Leonardo has always appeared in my life at the perfect moment. The first time was in 1956, when I started studying at the University of Fine Arts in Tokyo. My instinct told me that it was just a crossing point, even if getting into this university was a good opportunity for me. I think I heard Leonardo’s voice calling me at that moment’, he continues.

The young Susumu Shingu continued his university studies before heading to Rome with the aid of a study bursary from the Italian government. This was a transitional point in the creation of his artistic identity. Thus, he abandoned figurative painting for abstract 3D sculpture, before taking up sculpture activated by the wind. ‘After having started to focus on the creation of sculptures moved by the wind and water, Leonardo gave me some hints about different styles and techniques and sometimes gave me advice’, declares the artist who, like the Italian master, fills his sketchbooks with ideas throughout the day so as not to forget a single one.

A utopian village project

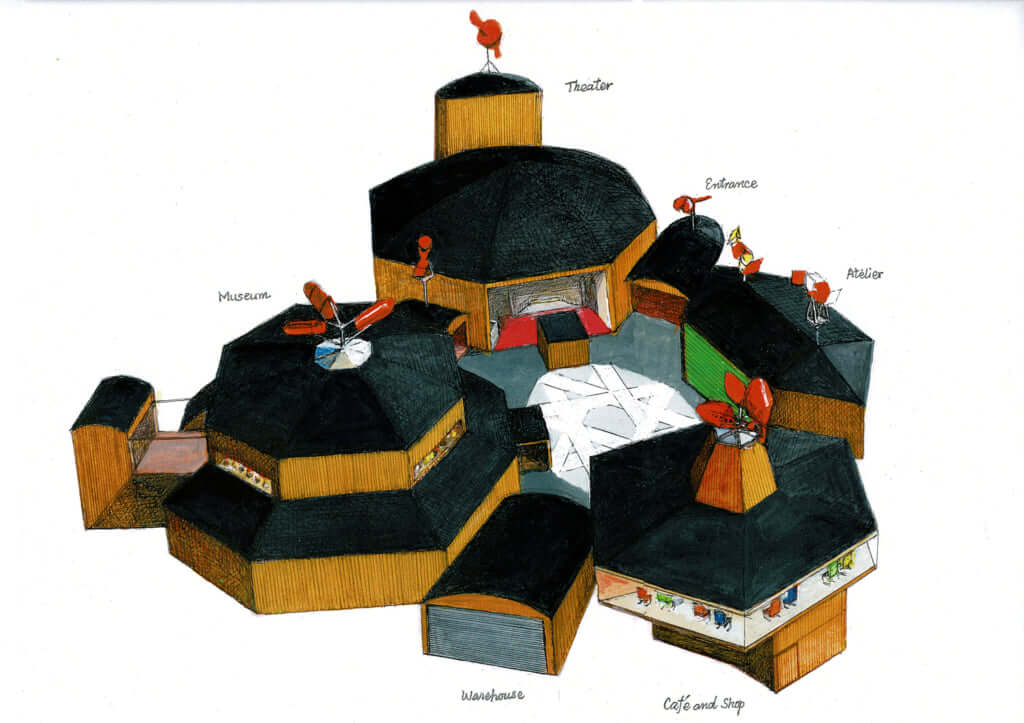

The Japanese artist, now in his eighties, has seen one of his most ambitious projects become a reality: the creation of a utopian village entitled Atelier Earth. Situated in the city of Sanda, north-west of Osaka in Hyogo prefecture, Atelier Earth encompasses a museum, a theatre, a workshop, and a café, all linked in a circle. And, of course, it bears the mark of the artist, as there is a coloured mobile sculpture at the top of each construction, some of which are connected to mechanisms that make it possible to move objects in the room.

‘I’m trying to create a workshop with people who share the same thoughts as me, without destroying nature further, as a place where we can take pleasure in thinking about a future way of life.’ This utopia could be seen to resemble that of da Vinci, when he designed a concept of an ideal city for Francis I of France. For Susumu Shingu, the priority is still, as always, this ode to and respect for nature.

Susumu Shingu: A Utopia for Today (2019-2020), was an exhibition that took place at Château de Chambord from 6 October 2019 to 15 March 2020. More information on Atelier Earth is available on the artist’s website.

Wind Museum Susumu Shingu (Sanda, Japan) 2015 © Jeanne Bucher Jaeger

Susumu Shingu, a utopia in Chambord © Susumu Shingu

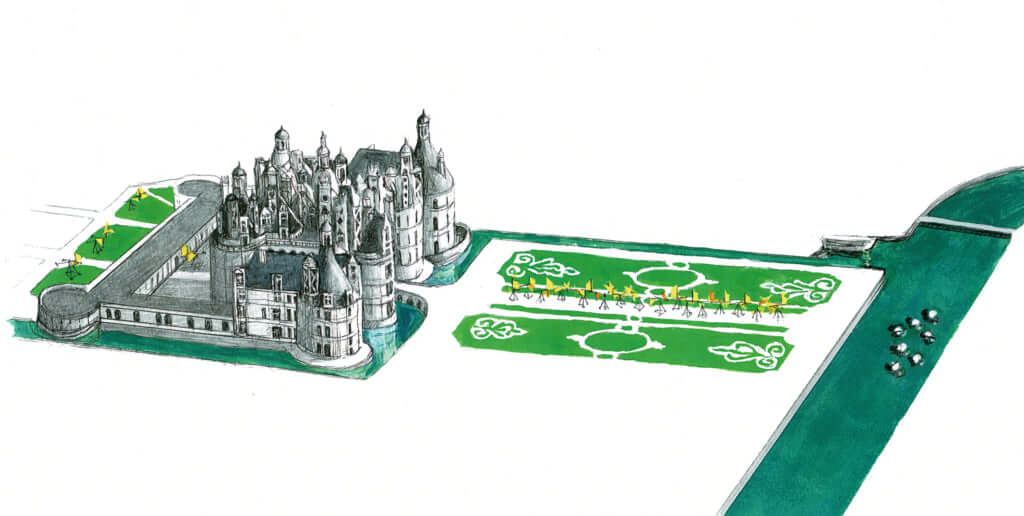

Susumu Shingu's drawing © Susumu Shingu

Atelier Earth drawing 2019 © Susumu Shingu

Susumu Shingu © Domaine national de Chambord - Olivier Marchant

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

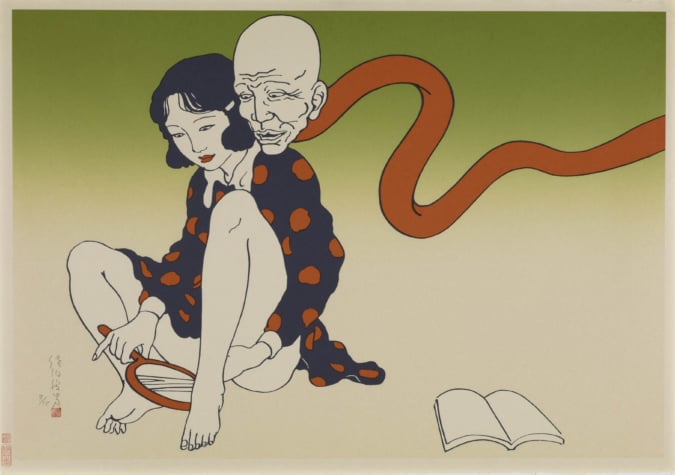

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.