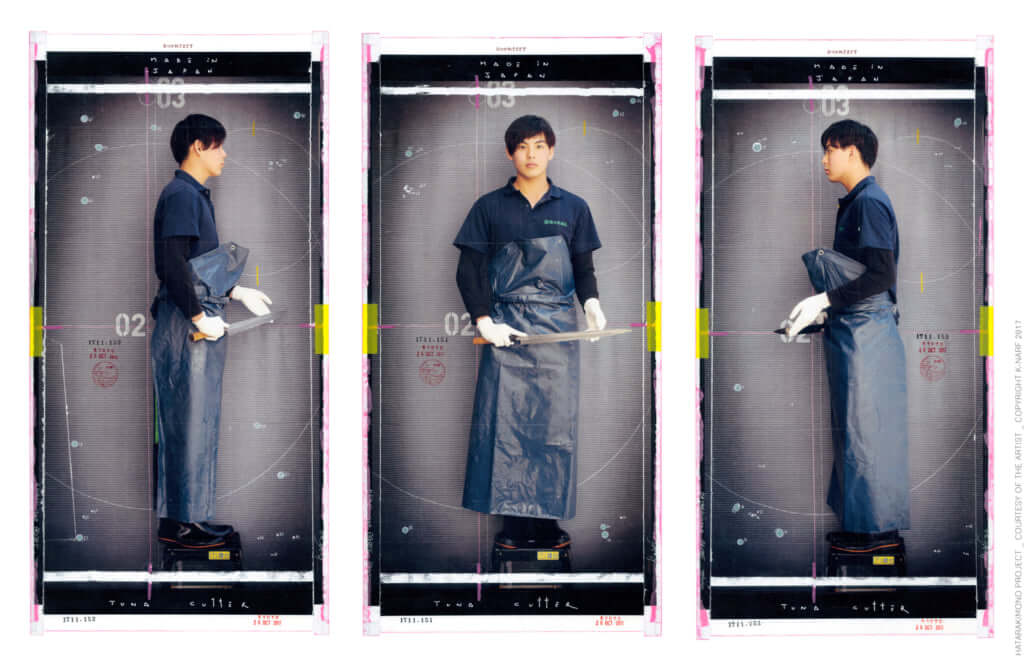

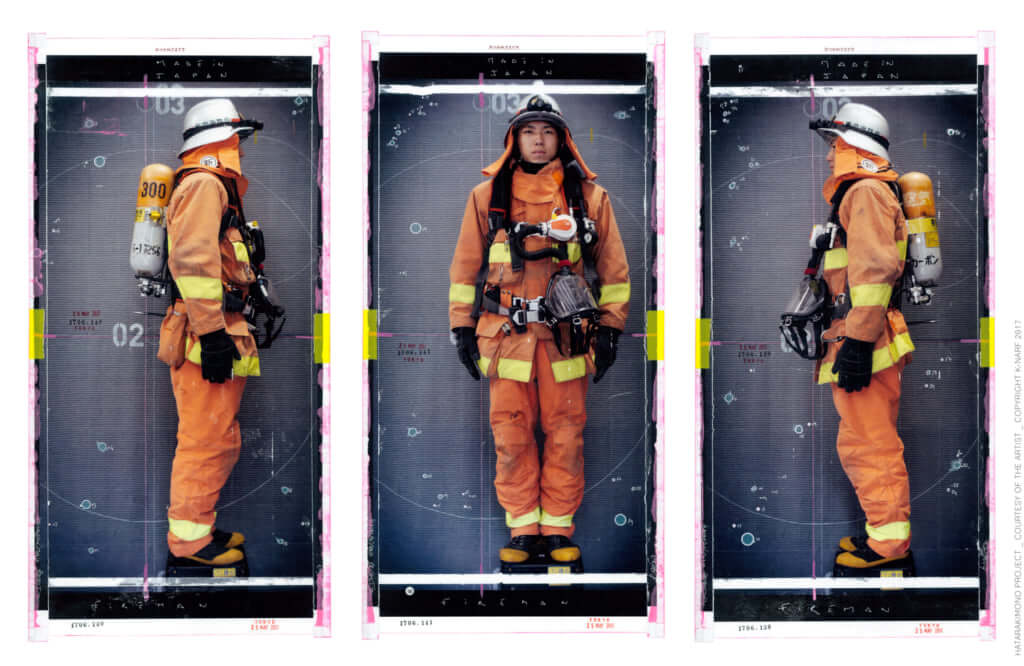

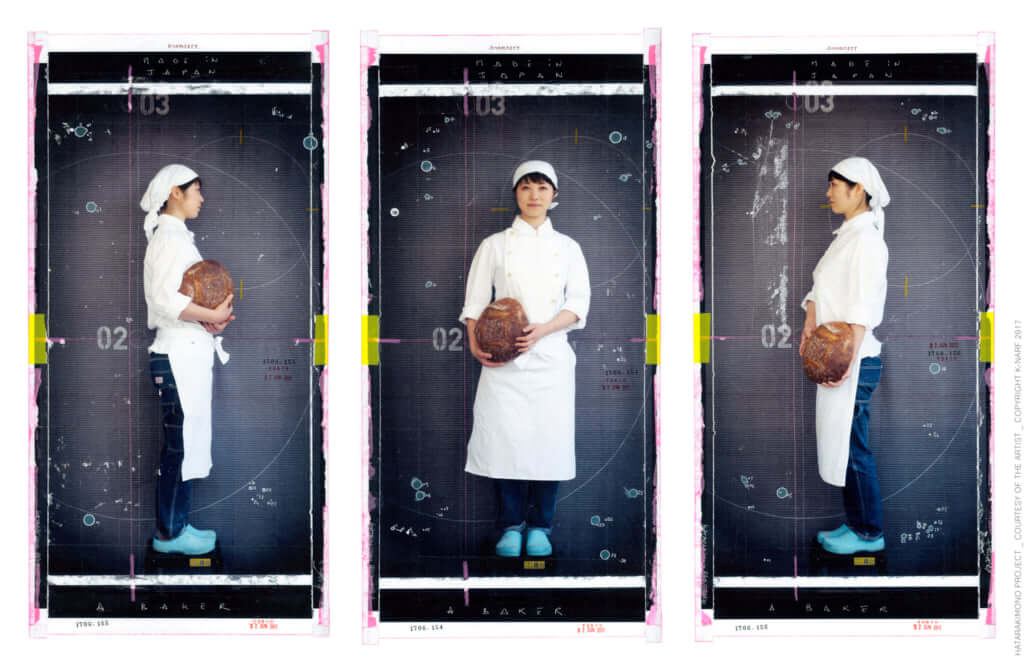

Hatarakimono: Portraits of Japanese Workers by K-NARF

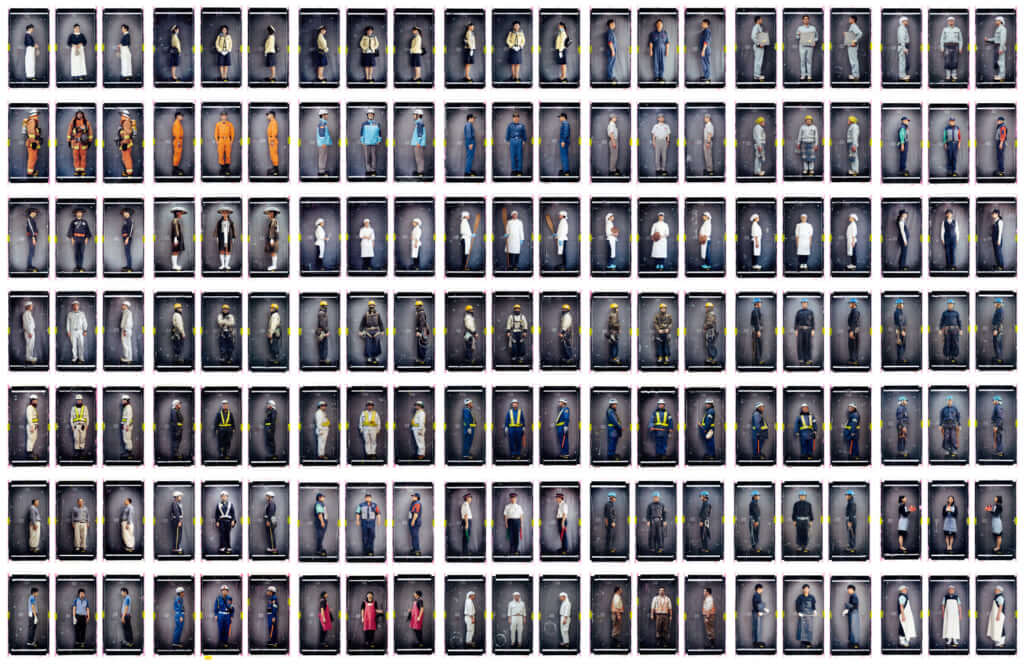

Transforming the Super-Ordinary into an Extra-Ordinary archive for future generations is the credo of K-NARF, a French artist who has been living in Tokyo for several years. With a hundred portraits of Japanese workers in uniform, Hatarakimono Project, his latest time capsule, bears witness to an upheaval in the world of work and immortalises trades that are doomed to disappear in a forward-looking Japan.

Who are Hatarakimono and why did you decide to photograph them?

‘This Japanese word, which is very unique and tricky to translate into English, means “hard worker.” With a positive and respectful connotation, the term refers primarily to a dedicated worker, who can be the boss of a large company or one of its employees. Residing in Japan, I realised that I was meeting Hatarakimono every day. The taxi driver, the supermarket cashier, or the lady in the elevator all provide excellent customer service. Yet the Japanese, and I with them, tend to pass them by without paying any attention.’

How did you select the workers and manage to convince them to take the pose dressed in their uniforms? Were you bold or circumspect?

‘Everything is very codified in Japan, so the longest and most complex part of the project was to get the authorisations. The workers were not hard to find and gladly agreed to pose. But they had to get their company’s approval; each company would release their employee for a few minutes, just long enough for me to take front and side shots. Shoko, with whom I carried out the whole project, was admirable and supported me in each of these steps.We work together like the artists Jeanne-Claude and Christo, and she is the one who asked for and obtained the authorisations, even those I thought were a lost cause, like the Ministry of Civil Security who authorised us to photograph the firemen.’

Are there still many Hatarakimono in Japan? Are they not threatened by new technologies?

‘The taxi driver will be replaced by a self-driving car; the cashier will be obsolete in front of an automatic cash register, and the delivery man will gradually become a drone. The disappearance of Hatarakimono is unfortunately inevitable. This fate is further aggravated by the ageing of Japanese society and a non-renewed workforce, with young people no longer aspiring to carry out the service professions of their predecessors. With Shoko, we even inquired about registering the Hatarakimono with UNESCO to ensure their preservation, but they cannot be classified as a single homogeneous group according to the institution’s criteria. Hence the urgency of making portraits of these workers, then preserving them for future exhibition, precisely 25 years from now.’

Why wait 25 years?

‘By 2042, the world will have greatly changed. We have already chosen and contacted five museums to display our exhibition: the International Center of Photography in New York, the British Museum in London, the Musée Guimet in Paris, the New South Wales Art Gallery in Sydney and the Nezu Museum in Tokyo. This process is an integral part of our project and we intend to present museum responses, only two having been received to date. While the Australian museum does not understand our approach, the British museum has apologised for not being able to comply with our request, since they do not have a photographic department.’

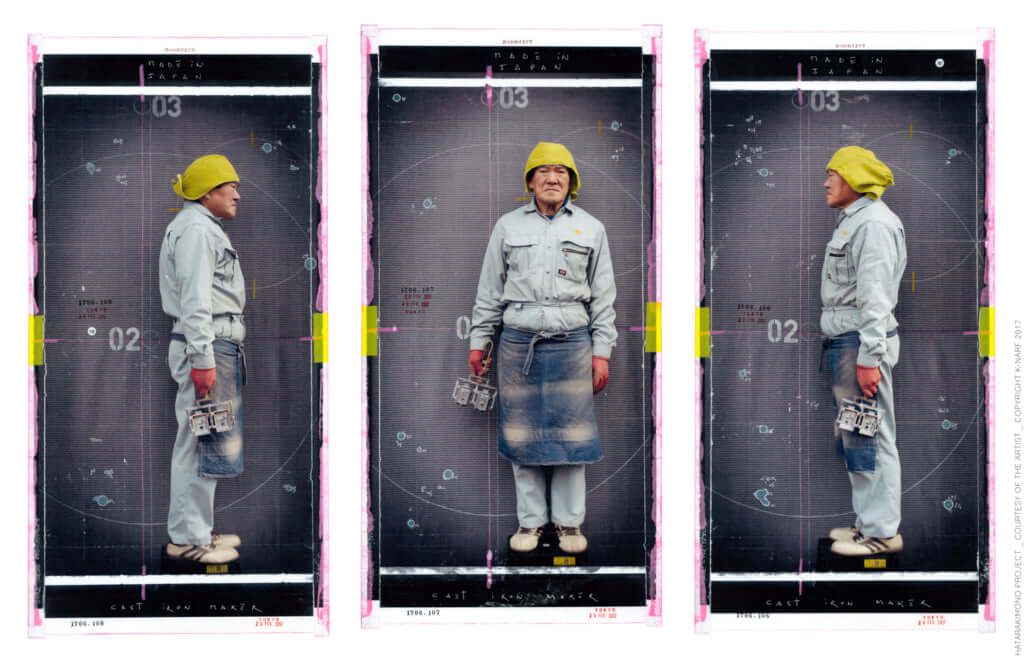

Would you explain the neo-vintage photographic development process you have developed, the ‘Tape-O-Graphy’?

‘My photographic work is part of the Bricolage Art Movement created by the American artist Tom Sachs. I use simple materials and totally amateur tools, without much value. With scotch tape and a small simple printer, I print my photographs and then I apply the adhesive, before pulling it off and appreciating the effects of its traces on the prints. This manual process gives a unique look to each tape-o-graph thanks to the imperfections that appear during development.’

Are there other facets of Japanese culture that intrigue you to the point of inspiring you?

‘The Hatarakimono Project has been a long-term project of almost three years, including two years of pure shots and development. We will now take a well-deserved break before considering a topic that is of particular interest to us: the use of plastics in Japan. The country is sadly the second largest consumer of plastics after the United States, and we would like to provoke some reflection on this issue.’

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

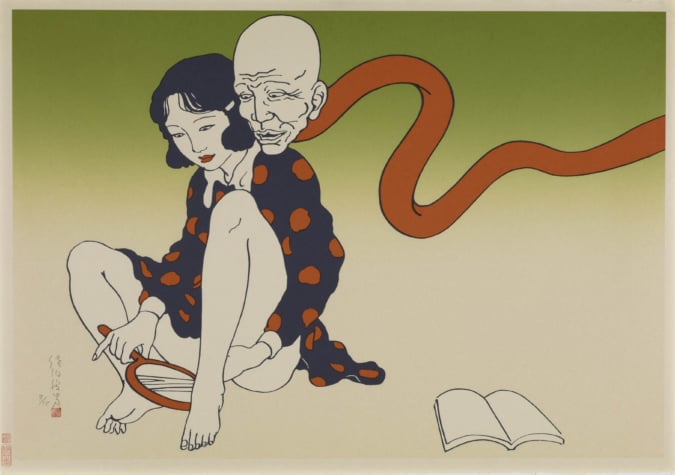

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.