Yoichi, sharing nature

This part of Hokkaido is the new paradise of Japanese wine with its emphasis on organic farming and sustainable agriculture.

Situated between Otaru and Shakotan, Yoichi is a natural area, close to the Sea of Japan, that faces the sun. It is also the new paradise of Japanese wine, as is made evident by the wide stretches of vines that cover its meadows and slopes. Here you will meet men and women from diverse backgrounds but who possess a shared interest in organic farming and sustainable agriculture.

©︎Pen International

No matter where you look, everything that the eye can see is vines. For those from Italy, France, or Napa Valley, the landscape is reminiscent of known territories. Springing to mind are the great wine regions in France: the Bordeaux region of course; Alsace; the hills along the banks of the Loire. Or Burgundy, if, like the winegrower François Servin, that’s where you were born and raised.

‘I came across this marvellous region of almost mountainous hillsides bordered by a coastline and a cold sea. The most astonishing thing for a Burgundian accustomed to Burgundy’s clay-limestone soil is the discovery of a virgin “terroir”, with black soil, rich and full of alluvium, making it a promising and fertile region’, says Servin. ‘But what is even more surprising’, he adds, ‘is Hokkaido’s unique climate. With freezing winters and hot and humid summers, the harvest is carried out delicately at the beginning of October, with the risk of more than abundant snow appearing a few weeks later. The climate is a terrible paradox for a land in the process of becoming a wine-producing area, as the snow makes access to the vines impossible for part of the year, and obliges the wine-grower to give up winter pruning for a preliminary green pruning, almost in defiance of the vine’s rest period. From the point of view of our French regions, it takes a very Japanese will, a very Japanese precision, to dare to raise vines in these regions.’

©︎Pen International

The rows and rows of vines obviously did not end up growing here by themselves. They are the fruit of long hours of hard work, and were only made possible through the force of impressive physical strength and an unwavering willpower. Servin continues, ‘On these hillsides we can find family ventures and small businesses, some of them micro-businesses, and some of them even producing just a few hundred bottles. But in every case we find enthusiasts! People who have had the “luck” to start their own story, to create a family legacy, to shape a future for their region, for their island. I say “luck” because, unencumbered by the weight of family tradition and ancestral customs specific to each appellation, they can afford to test, experiment, and create their own methods in the vineyard and in the cellar, and in the end invent their own wines.’

Take for example Shigeaki Kihara in the Mongaku Valley, who moved to the area with his wife and children after ten years of living an ordinary life in the international city of Tokyo. ‘I met my wife Yuko in Hokkaido, when we were both students here. When we graduated, we went to Tokyo, which seemed a necessary step for us, in order to discover the “salaryman” lifestyle and work in a company, that kind of thing. But we promised each other from the very start: ten years, and then we will return to Hokkaido. And that’s what we did.’

©︎Maximilien Rehm

‘The Japanese winegrower is more precise, more meticulous, than we can imagine,’ remarks Servin. ‘The grapes are painstakingly cut and examined, the seeds are separated and then they are delicately crushed. The wine cellars are like bourgeois Parisian living rooms—you walk through them in slippers! Hygiene is an important element here. And then there is the tasting. The winegrower will almost apologise for making you taste their “modest wine”, which makes it all the more surprising when you discover clear, fruity, promising wines. Of course, the terrain and the climate differ from what we know, but what a wonderful surprise, such perfection! Just as in the style of Japanese cuisine, which uses simple, immediately identifiable ingredients, the wines are straightforward and their aromas are varied. The white wines whet the appetite, while the reds are mouthwatering and easy to drink, reflecting the mood and personality of the winemaker.’

It would be impossible not to mention Takahiko Soga now, an ambassador for the region with his Takahiko estate. His wines, with ‘Nana Tsu Mori’ at the top of the list, are being sold from one end of the archipelago to the other and far beyond, often ending up on the tables of the best restaurants. It’s a complete package: devotion to the land, respect for life, and the desire—humbly but surely—to make his wine a piece of the terrain and the landscape.

‘The richness of the virgin soil, the diversity in the grape varieties used, and the precision of the Japanese winemakers give Yoichi wines an incredible finesse and purity,’ adds Servin. ‘We know that the Japanese are passionate about organic and “natural” wines. As a winegrower myself, I was extremely surprised and amazed by the attention to detail in the vineyard, the cellar, and the glass. In our regions, certain tastes and flavours of organic wines have yet to be defined, classified, and listed. Are these atypical aromas really characteristic of our grape varieties? Do they correspond to our terroirs? In the wine press this is a matter of debate, but in Japan, there is none of that! The wines that I have tasted in Hokkaido are crisp, sharp, and precise. Nothing strange, nothing atypical. Combining the richness from the new soils and the slopes, exposed to the sun and the wind, with a Japanese precision makes these wines marvellous, and is the best way to guarantee Yoichi a radiant future. Recently, the English journalist Tim Atkins asked me about my favourite wine. I have not one but three: Niki Hills Vineyards, Takahiko, and Mongaku Valley. I dare to say it loud and clear that my most striking tasting experience was neither a Burgundy nor a Bordeaux, but a Pinot Gris from Domaine Mont! It’s a shame to not see their wines available on French tables. That day will come! Didn’t they tell me that they wanted to make the region the “Japanese Napa Valley”? They are certainly capable of it.’

©︎Maximilien Rehm

Now it is late, and time for us to go back to our accommodation for the night: the Yoichi Eco-Village. Founded nearly ten years ago by Junka Sakamoto, the place is as much a part of the ecologist community as it is a micro-farm. It is situated only a few kilometres away from the Domaine Takahiko and Mongaku Valley vineyards. Their landscapes are different of course, as are their personalities, but we can find the same quiet determination, and the wild but strong, even joyful will to live alongside the land at one’s own pace.

Junka and his team—there are five of them during our visit, each with their own story and plan that drives them—talk about bio-dynamics, circular economies, and sustainable development. Utopia is never far away, in fact it is part of the plan. The place welcomes young and old, and not only those from Japan. Some come to spend a month or two here, some more. Many return year after year. Relationships are formed, which is also why we came here—to share and exchange.

The Eco-village is hands-on; the chickens must be fed at dawn, and the wire netting must be in place to protect them from the numerous foxes that prowl around here. A little reassured, we make our way to the small hut that will house us this evening. We are pleased with our day, and enriched by the new encounters, having collected so many stories to keep and share. Tomorrow is another day.

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

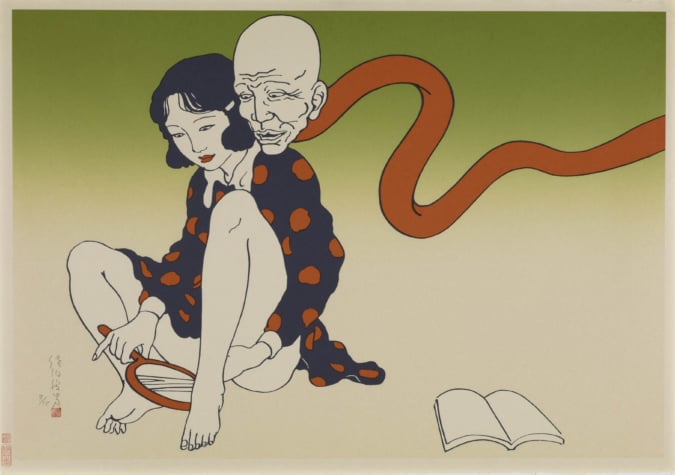

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.