Manga and LGBT Characters: Are We Witnessing an (R)Evolution?

‘I’m waiting for the day when a main character will belong to the LGBT community and this won’t be questioned. I’m waiting for the day when LGBT characters will just exist, rather than being a source of comedy or an incongruous presence’. According to Désiré·e, a bookseller who works at the Paris bookstore Ici and specialises in comic books/manga, this remains an all-too-common situation in manga, even though the representation of LGBT characters in manga has evolved somewhat in recent years.

‘Five years ago, we had to be content with characters that were quite one-dimensional. We had characters like Puri-Puri-Prisoner in One Punch Man, a predatory gay man, or Tooru Mutsuki in Tokyo Ghoul:re, a young transgender man who transitioned as a result of trauma’, Désiré·e explains.

Since then, some books have begun to represent LGBT characters in a less stereotypical manner. This is true of Blue Flag, which deciphers the journey through adolescence; one of the characters is gay, and another is a lesbian teenager. ‘It was published in Shonen Jump, a very popular magazine which features the best-selling series. The fact that this manga is published alongside major titles like The Promised Netherland and One Piece shows that things are slowly starting to change, even if there’s less visibility’, Désiré·e states. Éclat(s) d’âme is also a benchmark. In this manga, the reader follows various characters: a child questioning their gender, two lesbian women who would like to get married, and a young man trapped by his internalised homophobia.

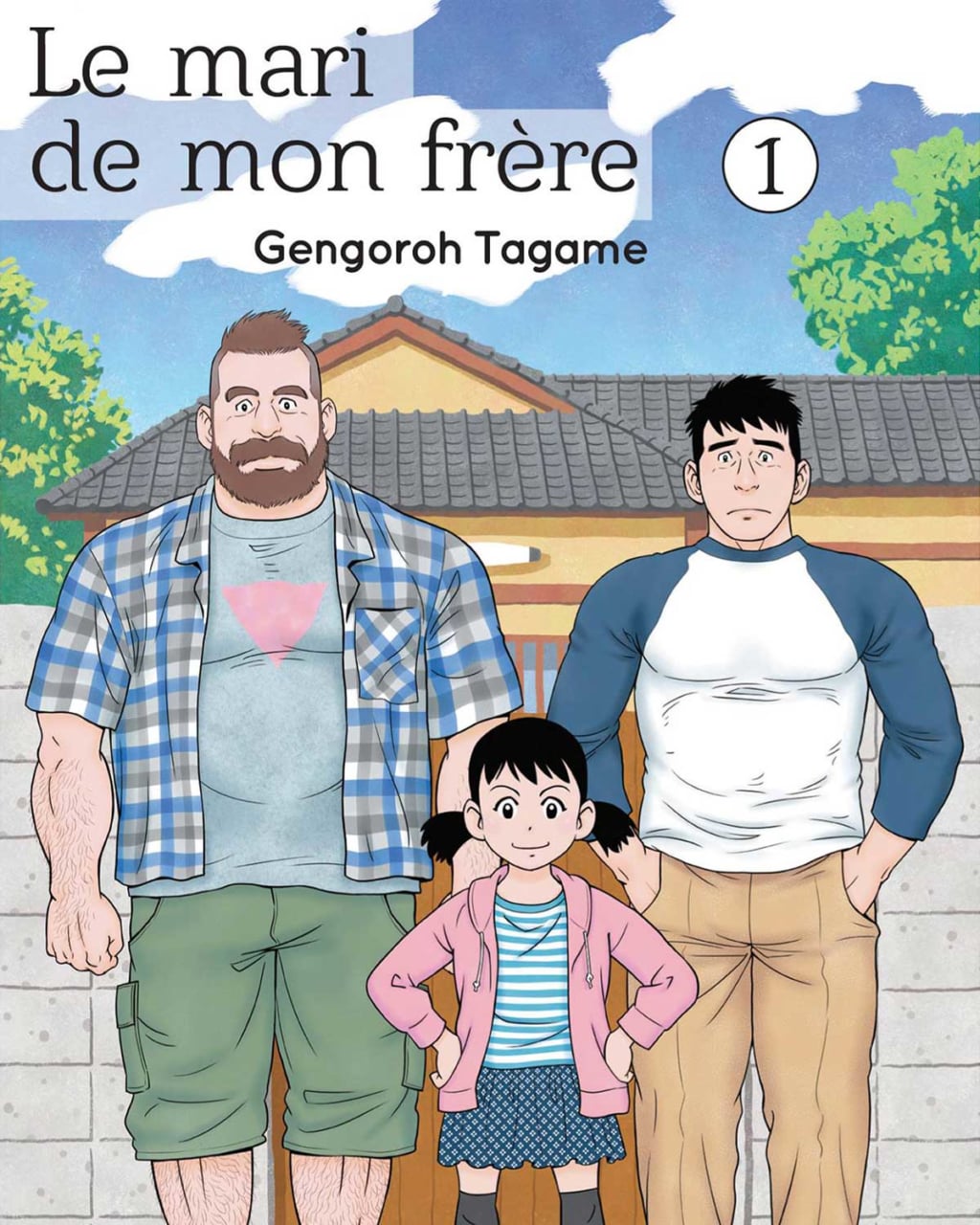

‘An increasing number of mangas are putting into words things which previously existed but which were absent from narratives. A few years ago, we didn’t even use the words gay or trans in an open and frank way’, explains Julien Bouvard, university lecturer in Japanese Language and Civilisation, specialising in popular culture, at the University Lyon 3. Some authors are even educating readers, like Gengoroh Tagama in his work My Brother’s Husband, which has educational content on gay culture interspersed between the chapters.

To gain an even deeper understanding on the evolution of manga that has occurred in recent years concerning the representation of LGBT characters, we need to go back to the 1970s. This is when Boys’ Love (also known as Yaoi), mangas written by women and for women, and which presented masculine gay characters, became hugely popular. ‘In that decade, a group of female mangakas, notably Riyoko Ikeda, really took off and started to take interest in romances between young boys’, explains Julien Bouvard. It was an important moment with regard to the issue of representing gender and sexuality, as these mangas were very far from the hetero-centric perspective typically adopted in mangas. ‘It’s the only solution that remains when you don’t identify with the violent and degrading representation of female bodies. So authors began to objectify the male body instead and to reverse the roles, by modifying their sexuality and aesthetising the male body, which became very feminised’.

This diversion from masculine norms was warmly welcomed by female readers. ‘It was a very political but nevertheless unconscious choice because when we speak to female readers, they stress the pleasure they take from reading a book that is disconnected from their sexuality, from taking interest in a different sexuality, but without necessarily seeing themselves as being engaged with the LGBT cause’, Julien Bouvard explains. Gay readers, however, have reacted to this new genre in a more ambivalent way. Some emphasise that Boys’ Love simply promotes what is still a very stereotypical image of what a homosexual should be. This follows the example of Sata Masaki, a gay militant who, in the 1990s, admitted to a publication specialising in gay issues his desire to see these romances disappear. ‘This shows the tensions between gays who feel dispossessed of their representation by heterosexual women who are simply having fun, and others who might find it a positive thing to see themselves represented in a work’, explains Julien Bouvard.

This very stereotypical vision is one that society seems to have been gradually emerging from since the 2010s. Which then leads us to ask: who draws and constructs the narrative? Gengoroh Tagama is a gay mangaka, while Yuhki Kamatani, the mangaka behind Éclat(s) d’âme, is non-binary. Are these LGBT authors the best guarantee of a representation of LGBT identities that’s free from any form of distortion? Which might then pave the way for other mangakas to cease to represent LGBT characters as abnormal or marginalised?

This question goes hand in hand with the observation of the advancements that have been made in Japanese society with regard to these issues, for which popular culture might act as a good mirror. ‘Popular culture reflects a part of society: everything depends on who creates it and consumes it. In a sense, mangas – however they’re produced, whatever their content, whatever the status of the author and the reader – are evolving with Japanese society’, declares Aline Henninger, lecturer in Japanese Language and Civilisation at the University of Orléans. ‘But we mustn’t forget that an integral part of this huge editorial market presents fictional narratives and doesn’t necessarily intend to show social reality. It’s a bit like if we tried to say that Black and Mortimer was an accurate reflection of Belgium’.

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

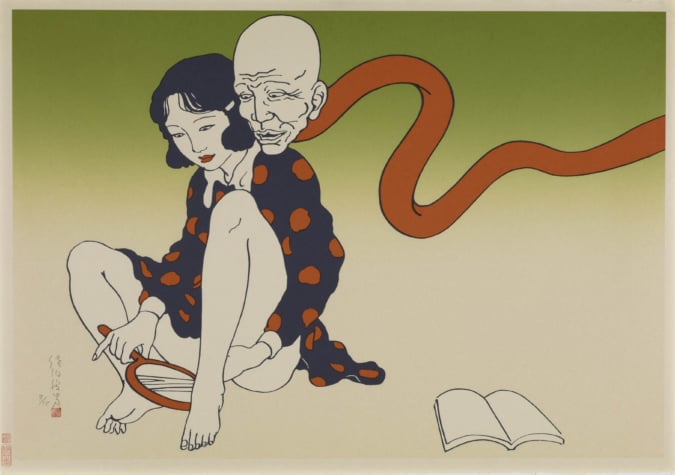

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.