Suspended Moments in Ozu’s Cinema

Pillow shots, those brief scenes that feel almost out of time during films, are a hallmark of Japanese filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu.

‘Late Autumn’ © 1960-2013 Shochiku-Co.-Ltd.

In his films with minimalist plots and which seem to aim to be pared down, Yasujiro Ozu adds brief pauses. During the narrative, he inserts short moments that feel as if they are almost suspended, motionless images. Film historian Noël Burch refers to these as ‘pillow shots’ in his book To the distant observer – Form and meaning in Japanese cinema, and they are sometimes also described as stasis or still lifes. They create another time, one which is not exactly the same as that seen in the plot, but which is also not entirely foreign to it. Noël Burch sees these pillow shots as instants that ‘suspend the diegetic flow, without ever contributing to the advancement of the plot per se’, while philosopher Gilles Deleuze describes them, in Cinema – The Time-Image, as a ‘representation of time’.

Shifting the viewer’s gaze

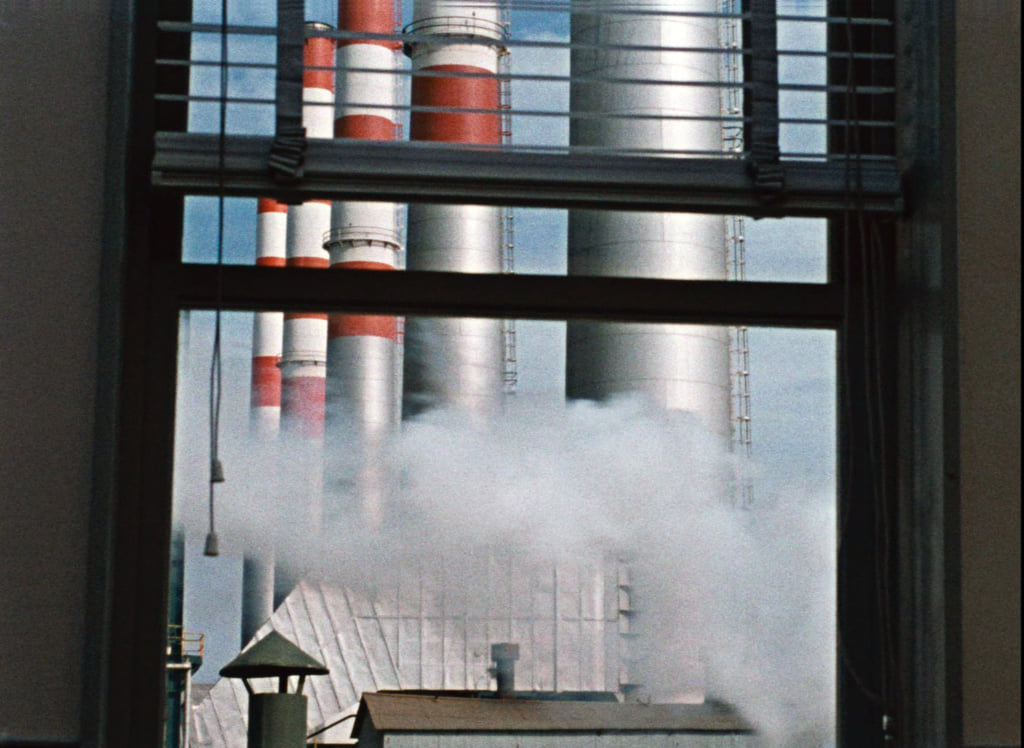

Thus, these floating shots interrupt the movement. The actors disappear from the screen and instead the focus falls on everyday objects, an interior, road signs, or a cloudy sky, for a handful of seconds snatched away from the plot before the protagonists then potentially reappear. It’s a subtle balancing act between full and empty space.

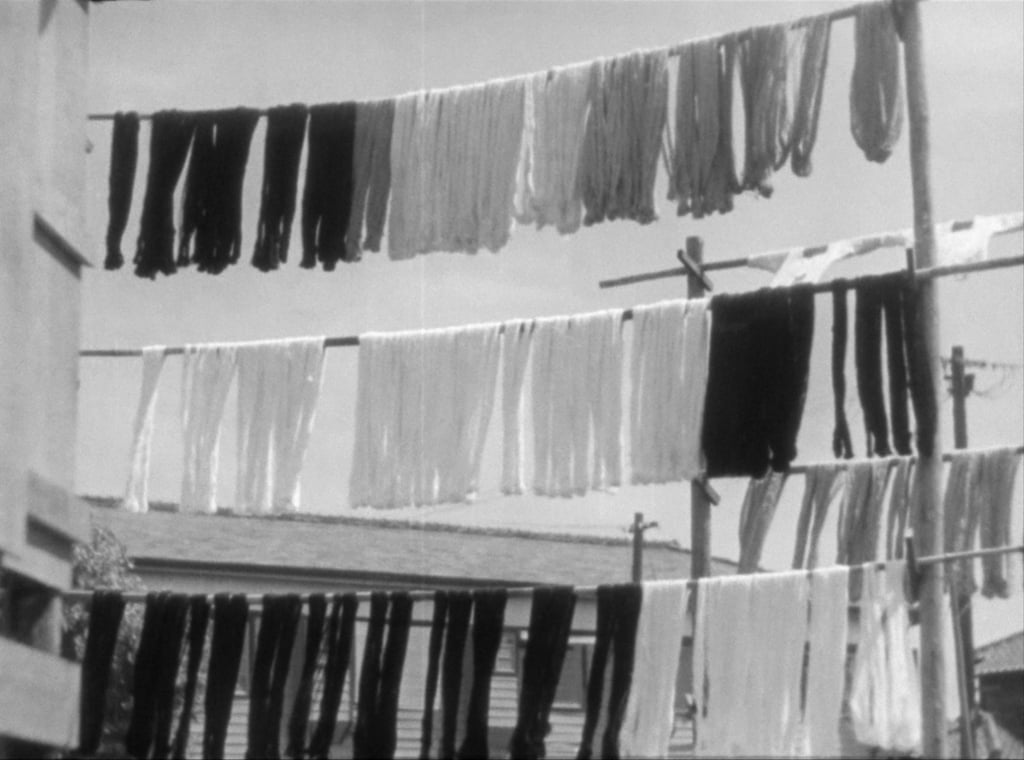

Some pillow shots particularly stand out. The long shot of a porcelain vase in Late Spring (1949), the laundry blowing in the wind on a washing line in Good Morning (1959), or the dark corridor at the end of which we can make out a person lost in their thoughts, like an introduction to or a clue about the scene that’s to come in An Autumn Afternoon (1962). A kettle, a lantern, a pagoda, and empty spaces are used as tools to better understand the plot, which each viewer can imagine in their own way.

Yasujiro Ozu has another hallmark: his specific way of always placing his camera at around 90 cm off the ground, around the height of a man sitting on a tatami mat, which allows his films to be identified at a glance. These subtleties, among others, explain the fascination with Ozu’s cinema, even though France only discovered it in 1978, 25 years after Tokyo Story was filmed.

Noël Burch analyses pillow shots in his book To the distant observer – Form and meaning in Japanese cinema, 1979, available for free on the website of the University of Michigan Library.

‘The Only Son’ © Shochiku-Co.-Ltd.

‘An Autumn Afternoon’, restored version © Shochiku-Co.-Ltd

‘An Autumn Afternoon’, restored version © Shochiku-Co.-Ltd

‘An Autumn Afternoon’, restored version © Shochiku-Co.-Ltd

‘Good Morning’ © 1959-2013-Shochiku-Co.-Ltd.

‘An Autumn Afternoon’, restored version © Shochiku-Co.-Ltd

‘An Autumn Afternoon’, restored version © Shochiku-Co.-Ltd

‘The Only Son’ © Shochiku-Co.-Ltd.

‘An Autumn Afternoon’, restored version © Shochiku-Co.-Ltd

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.