Florent Weugue, a Tea Sommelier in Japan

‘Tea is a work of art and needs a master hand to bring out its noblest qualities’, wrote Kakuzo Okakura in his work The Book of Tea. This statement is reinforced by Florent Weugue, a leading figure in the specialised field of Japanese tea. Fuelled by the art of living through tea, which incarnates purity and refinement, Florent became, in 2009, the first French person to be certified as a Nihoncha instructor, or ‘Japanese tea sommelier’.

Keen to dispense his advanced expertise in the subtleties of Japanese tea, he is responsible for selecting tea products and accessories for the online shop Thés du Japon (Teas of Japan). In his free time, he shares his knowledge and discoveries on his two blogs, in English and French, in order to familiarise readers with the richness and depth of Japanese teas.

Pen Magazine spoke to Florent Weugue to find out more about his role as a Japanese tea sommelier.

How do you become a tea sommelier in Japan?

The ‘Nihoncha Instructor’ certification (Nihoncha means ‘Japanese tea’) is awarded after two exams. The first is a written, theoretical exam which tests your overall knowledge about tea (agriculture, manufacture, history, infusion methods, chemistry, etc.), and the second is a practical exam which tests your ability to recognise and evaluate tea (type, harvest period, etc.).

Where does your interest in tea stem from?

I’d had a certain degree of interest in tea for quite a while but hadn’t taken a special interest in it before I arrived in Japan. After that, I had the chance to try teas which I found I liked a lot, and which made me want to find out more. Unfortunately, none of the Japanese people I knew had even the slightest knowledge about tea, which meant that I had to study it myself and buy books about Japanese tea, which opened my eyes to this rich, fascinating world. I met passionate tea specialists, and ended up becoming a big fan of Japanese tea myself. Looking back, I think that if the Japanese people I knew had been able to explain the basics to me, I would never have discovered tea in such depth. I was encouraged by a renowned specialist to become the first French and one of the first foreign ‘Japanese Tea Instructors’, in order to have some real training, and with the unspoken aim of perhaps making a career out of it.

Were you instantly welcomed into the inner circle of tea experts in Japan, or did you have to carve out a place for yourself as a foreigner?

The fact that I spoke Japanese and had a recognised certification in tea was a real help, but finding work in this area was more difficult as it didn’t escape the crisis. It took me a few months to find my first job with a company which owned several boutiques in the Tokyo region. However, when I had to buy supplies for the Thés du Japon boutique, I instantly made very good and positive contacts. Now, the world of Japanese tea has become far more global and is looking for new markets, which is a direct consequence of the significant crisis that tea experienced in Japan in the 1990s.

What would be the ideal tea to drink whilst reading Pen Magazine?

Generally speaking, there’s no such thing as an ideal tea. The range of flavours, the regions of production, the plant varieties and many other factors come into play, so it’s all a question of taste and your mood at a given time. But I’d recommend an elegant sencha; it’s light in the mouth but very fragrant, with a light torrefaction process.

What is your favourite tea?

Again, I prefer to enjoy the almost infinite variety of flavours that tea offers. At the moment, I particularly like a sencha tea from Shizuoka that’s made from Benifûki (which is in fact a variety of black tea), which has a floral, fruity scent that’s really rich and surprising.

I’ve also become very interested in Japanese black teas recently, a variety of tea that’s developing and that’s improved in quality considerably over the past few years.

Which regions of Japan are the most favourable for tea production?

Tea is produced almost everywhere in Japan. It’s difficult to say that one region is more favourable than another, even if it is true that there aren’t really any key producing regions beyond Saitama and Ibaraki. Each production zone has developed growing habits and manufacturing styles which are more or less different, but the quest for diversification has tended to reduce regional characteristics. Shizuoka is a clear example: it’s the most important producing area in Japan, with teas grown in the mountains which are radically different to those grown on the plains, in plantations which are sometimes just a few kilometres apart.

Where should you start if you want to get into Japanese tea?

It’s easier said than done for people who don’t live in Japan, but you should start by trying as many different teas as possible, focusing initially on sencha. You have to understand tea while paying no heed to the cliches around it that are all too present in the West, and concentrate on the taste, rather than any stories you hear. You need to try to understand the main elements which make a big difference when it comes to the flavour (shade, steaming, torrefaction, plant varieties, etc.).

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

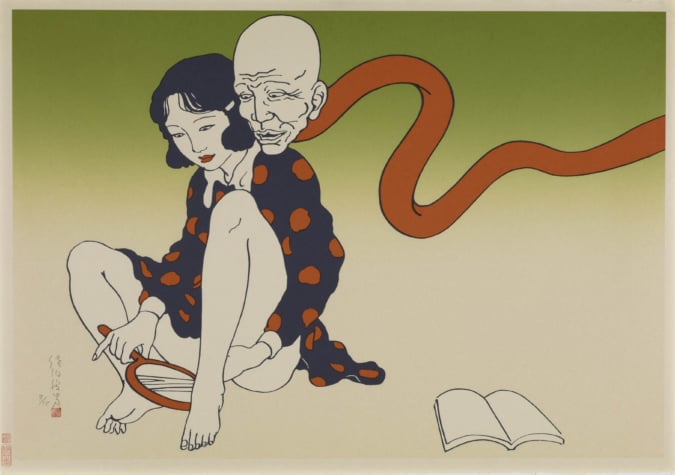

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.