Hiroshi Sugimoto, Where Noh Theatre Meets Ballet

©Ann Ray

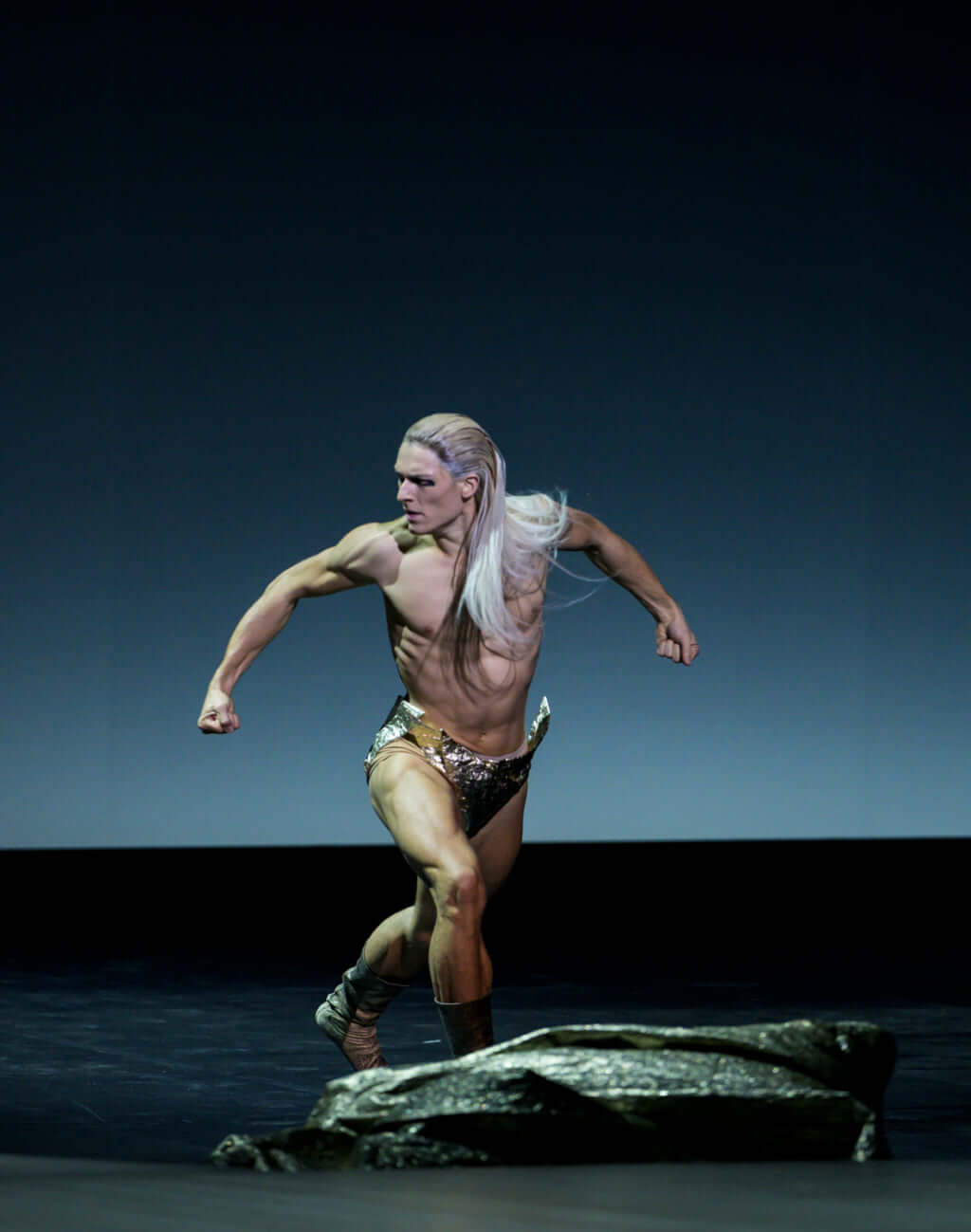

Shadow puppets in the form of mythological figures moving across the stage, an old man waiting, the disorientated young hero and a fiery bird shake up the arrival of a shite actor who has come straight from Noh theatre. This is the basic outline of the play ‘At the Hawk’s Well’ staged and directed by Hiroshi Sugimoto for the dancers at the Opéra National de Paris.

The Japanese photographer and artist is known for his photos of seascapes in which the horizon line blends in with the sky, but here he is taking on the work of a late 19th-century Irish poet, William B. Yeats. The latter was one of the first people in the western world to take an interest in Noh. Yeats sought to renew the conventions of classical western theatre and found the modernity it was lacking in its Japanese equivalent. Between 1916 and 1919, he wrote four plays inspired by Noh, and one of these was ‘At the Hawk’s Well’. The play was first performed in 1916 in a socialite’s drawing room, with dancer Michio Ito playing the role of the shite. It was a firm success and would go on to be adapted over the years, notably to be accompanied by Noh music.

The story deals with central issues in life and death. On a secluded island, on the edge of the sea, is a well which contains the water of immortality. An old man waits here to finally take his turn to drink this liquid of life. But the well is closely guarded by a hawk-like woman who plunges him into a deep sleep whenever the water rises. When the young hero Cuchulain comes to try his luck at the well, the hawk-woman appears and he heads off in pursuit of her. In the end, nobody manages to access the immortality they so desire.

‘These performances at the Palace Garnier are my attempt to bring the spirit of Yeats back to the stage thanks to the wonderful dancers of the Paris Opera’, Sugimoto writes in the programme for the play. And he does this with brio in a production which echoes his sea scenes thanks to screens hung in a semicircle at the back of the set upon which light effects are projected, thus recalling his photographs. A Nogakudo, the traditional raised stage found in Noh theatre, has been erected specially for the occasion at the front of the performance area to represent the island in the story. The three characters all launch into a highly modern variation which revisits the conventions of ballet, brought out by the music of Ryoji Ikeda. The ports de bras with the elbows bent at a 90-degree angle contrast sharply to the fluidity of classical dance. The same is true for the costumes made from lamé fabric which form what look like giant covers in which the dancers roll themselves up. They use them in their precise gestures which are a clear tribute to Noh dance.

Of course, there is the interlude with the shite. Here, too, the audience can spot certain breaks with tradition. Choreographer Alessio Silvestrin, who has been living in Japan for many years, took some liberties with the form. He states that he took inspiration from the Buddhist paradox that ’emptiness is form, form is emptiness’ and transformed it into ’emptiness is form after form is emptiness’. Two Noh theatre actors, Tetsunoji Kanze and Kisho Umewaka, made the trip from Japan especially to play this incongruous character, but one who is magnificent when he appears in the finale of the play, just like in Noh plays.

‘At the Hawk’s Well’ is not Hiroshi Sugimoto’s first venture into scenography; nor is it his first collaboration with the Opéra National de Paris. He is becoming increasingly enamoured with the performing arts, and audiences have had the chance to admire his work in adaptations of traditional Japanese plays, ‘Love Suicides at Sonezaki’ (2013) and ‘Sambaso, Divine Dance’ (2018), staged as part of the Paris Autumn Festival. More recently, he invited Aurélie Dupont, dance director of the Opéra de Paris and former star dancer, to perform ‘Ekstasis’, choreographed by Martha Graham, on the roof of the Enoura Observatory, designed by his foundation in Odawara. The video of ‘Breathing’, a parenthesis in time and space, perfectly illustrates how Sugimoto sees Noh:

‘Noh theatre is an art which makes time fluid. Time passes in one direction, from the past towards the future; but Noh is exempt from this constraint, it moves freely in time, like a time machine. In Noh, dreams act as a vehicle, which is why certain types of Noh are described as fanciful.’

©Ann Ray

©Ann Ray

©Ann Ray

©Ann Ray

©Ann Ray

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.