The Awe-inspiring Nature Protects Ise Jingu

Ise-Shima: The Homeland of the Japanese Soul #02

The sun glistens onto the Kotaijingu (Naiku).

Mie Prefecture lies virtually in the centre of Japan’s Pacific coast, and Shima Peninsula is situated in the central eastern portion of the prefecture. Ise-Shima National Park, the beauty of which stems from the interwoven mixture of human cultivation and Mother Nature, both on land and at sea, covers the whole peninsula. Ise Jingu, Japan’s largest Shinto shrine, occupies the central part of Ise-Shima.

‘Although invisible, there is always someone or something protecting me at my side. Just feeling that way makes me so thankful that my eyes are brimming with tears’.

Those words were written in a waka poem composed during a visit to Ise Jingu by the famous poet Saigyo Hoshi (1118-90), who renounced his position as a noble samurai at age 22 to convert to Buddhism and become a monk. The premises of the shrine undoubtedly inspired the subtle sensitivity of this 12th-century intellectual to feel such awe, thankfulness and appreciation.

What is it about Ise Jingu that gives it such a sense of being a ‘sanctuary’? An important element of that is the natural setting that envelops the jinja.

Spring kagura dances are staged in late April. The beautiful dances are performed featuring the nature of Ise Jingu as a backdrop, including brilliant cherry blossoms.

Deer appearing on the grounds of Naiku.

The grounds of Ise Jingu are divided into the shin’iki (holy precincts) and kyuikirin (Ise Jingu precincts forest). The nature within the shin’iki is managed with the aim of preserving the dignity of Ise Jingu. Meanwhile, the kyuikirin is cultivated as a forest with the aim of protecting the quality of the water flowing in the Isuzugawa River and the natural beauty of Ise Jingu.

The expansive area of the shin’iki is brimful of special must-see sights no matter what season you may visit: the vividly fresh verdure and beautifully blooming flowers of the spring, the deeper greens of the summer, the kaleidoscope of colours in the autumn, the snow-brushed jinja architecture in the winter, and so forth. A prime attraction of Ise Jingu is the ability of visitors to enjoy the quintessentially Japanese change of seasons with all their senses.

The flaming colours of autumn leaves adorn the banks of the Isuzugawa River.

The bridge leading to the Kazahinominomiya is often covered with snow during winter.

The kyuikirin forest lies in the upper reaches of the Isuzugawa River that flows next to the Kotaijingu (Naiku). Spreading over a vast area of 5,500 hectares, the forest plays another special role, namely, that of providing the special lumber—known as gozoeiyozai—needed for the Shikinensengu, which is the series of rituals of the regular reconstruction and relocation of the main Ise Jingu buildings at a preordained interval of twenty years.

The enormous kyuikirin forest that surrounds the precincts of Ise Jingu.

Under the Shikinensengu system, a ceremony takes place at Ise Jingu every twenty years in which the divine palace is rebuilt at a new site, alternatively to the east or the west of the previous site. Everything is carried out according to traditional building techniques, with the divine palace being totally reconstructed and the clothing and treasures therein also remade, after which the deity Amaterasu Oomikami is finally transferred as well. The system began around 1,300 years ago at the decree of Emperor Temmu (who reigned 673-86), Japan’s 40th emperor, with the first reconstruction taking place in 690 during the 4th year of Empress Jito’s reign. The tradition has continued ever since then, with the most recent Shikinensengu of 2013 representing the 62nd time it has taken place.

Originally, the gozoeiyozai special lumber used in the construction was supplied from the kyuikirin forest whenever the Shikinensengu divine palace rebuilding and relocation took place, but starting in the 14c, good-quality hinoki cypress was no longer available, so it started to be procured instead from local mountains and elsewhere. In 1923, though, a plan was hatched at Ise Jingu to manage the kyuikirin forest in a way that gozoeiyozai special lumber could again be supplied as in the past, with the goal of growing hinoki cypress that could be used in the next two hundred years. As a result, during the Shikinensengu of 2013, the kyuikirin forest supplied a quarter of gozoeiyozai special lumber for the first time in approximately seven hundred years.

A hinoki cypress tree in the kyuikirin forest being lovingly tended to. Those trees that demonstrate promising growth traits are marked with special paint. Courtesy of Jingushicho

People working hard to plant the trees, with a view of how they will turn out two centuries from now. Courtesy of Jingushicho

Amaterasu Oomikami is the ancestral deity of Japan’s Imperial Family, and by extension she is ultimately the tutelary deity for the whole Japanese population, seen as one big family. Ise Jingu, which enshrines her sacred presence, along with the natural setting that encompasses it, still maintains their overwhelming beauty today. Without doubt, the ethereal experience of being ‘so thankful’ that your ‘eyes are brimming with tears’ awaits you as you are exposed to the sublime nature that protects the eternal sanctuary.

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

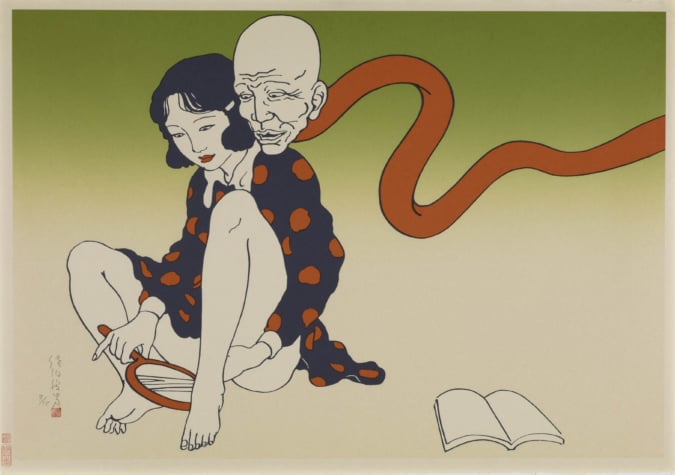

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.