Might We See The End of The Salaryman In Japan?

©Ryoji Iwata

A tide of men in suits and ties make their way through the tentacular corridors of the Japanese subway at rush hour. These men, collectively called salarymen, are the emblem of a triumphant post-war Japan and exemplary economic success. But for how long?

In Japan, the world of work is regulated by the implacable post-war economic model which consists of recruiting future white collar workers as they graduate from university. Companies can then ensure themselves an efficient workforce that owes them their allegiance and devotion until the end of their career in exchange for guaranteed work for life.

The type of employee represents his company with pride, with impeccable dress of suit and tie and the most considered behaviour and gestures. In order to prove their allegiance, many of these workers refuse to take all of their paid holiday in order to maintain a good relationship with their employer. If an employer takes all his holiday, it is an implicit message that he doesn’t hold his company in particularly high regard.

©Francesco Ungaro

While the Japanese government recently adopted a law to increase the number of obligatory holiday days, still a number people are refusing to abide by this new rule in order to avoid work falling to colleagues in their absence. This mentality, prioritising collective interests over individual ones, is specifically Japanese and has its roots in 5th and 6th century shinto and buddhist doctrines which describe work as one of the most important societal values.

In the work The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, anthropologist Ruth Benedict describes Japanese servitude as a force of character which shows through in the obeying of rules, not through revolt. Dedicated to their company, these tireless Japanese workers see a colossal number of overtime hours pile up, considered a testimony to their loyalty and engagement. Even if the day’s tasks have been fully accomplished, the norm is that the employee never leaves his office before his boss. Similarly, once the day is over, it is habitual for colleagues to find themselves in an izakaya, to decompress and drink heavily before returning home on the last train.

©Max Anderson

However, this accumulation of work can have harmful consequences. The Japanese government has reported 200 cases of karoshi each year, a number that is far below the sad reality. Karoshi, composed of ka for excess, ro work and shi death, designates death by overwork. To counter this scourge, the Japanese government is trying to implement certain practices such as obliging bosses to turn off the lights in offices at 10 p.m. and to encourage their employees to leave their workplace at 3 p.m. every last Friday of the month. The number of overtime hours has also been limited to 100 hours per month, but the risk of karoshi is increased tenfold from 80 hours of overtime per month.

Japanese security company Tasei is tackling the problem head on, using an unusual process, they use a drone that chases the last office workers by playing the Scottish song Auld Lang Syne, usually used to announce the imminent closure of stores to customers. A sign of increasing awareness about the problems of the world of work, is the popularity of the series Watashi Teiji, translatable by ‘I will not work overtime’. It depicts the life of an employee in her thirties who desperately tries to leave her job at 6 p.m. each evening, without ever succeeding.

If the life of a salaryman was previously seamlessly regulated, this foolproof bondage no longer suits the younger generation. Rather, they dream of being able to reconcile personal life with a professional career and thus to depart from a life entirely dedicated to work.

©Charles Deluvio

©Alva Pratt

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

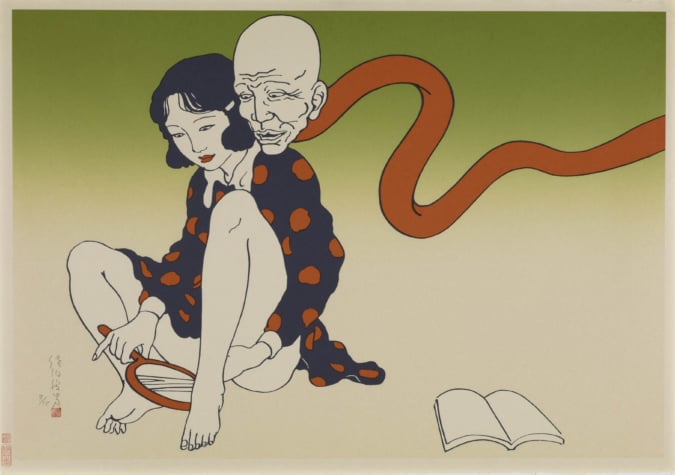

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.