When Friendship Repairs the Damage Done to the Deceased

In the manga ‘My Broken Mariko’, Tomoyo cannot stand idly by following the death of her best friend, a victim of violence.

©Waka Hirako 2020 / KADOKAWA CORPORATION

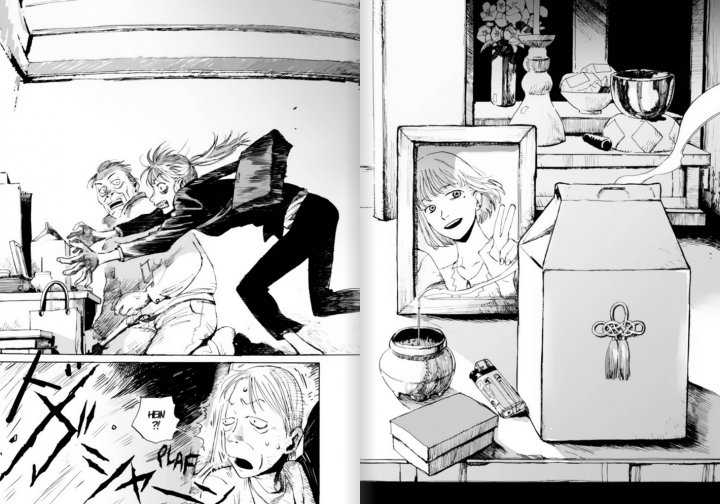

The opening scenes pass in quick succession, in a stark manner. The reader soon learns that Mariko’s death was unjust, that she had experienced countless atrocities at the hands of her father since childhood and that after her death, her closest friend Tomoyo could not bear to leave her ashes in his possession. Thus, she steals them from the hands of paternal authority and heads off armed with this little urn, determined to pay homage to the deceased.

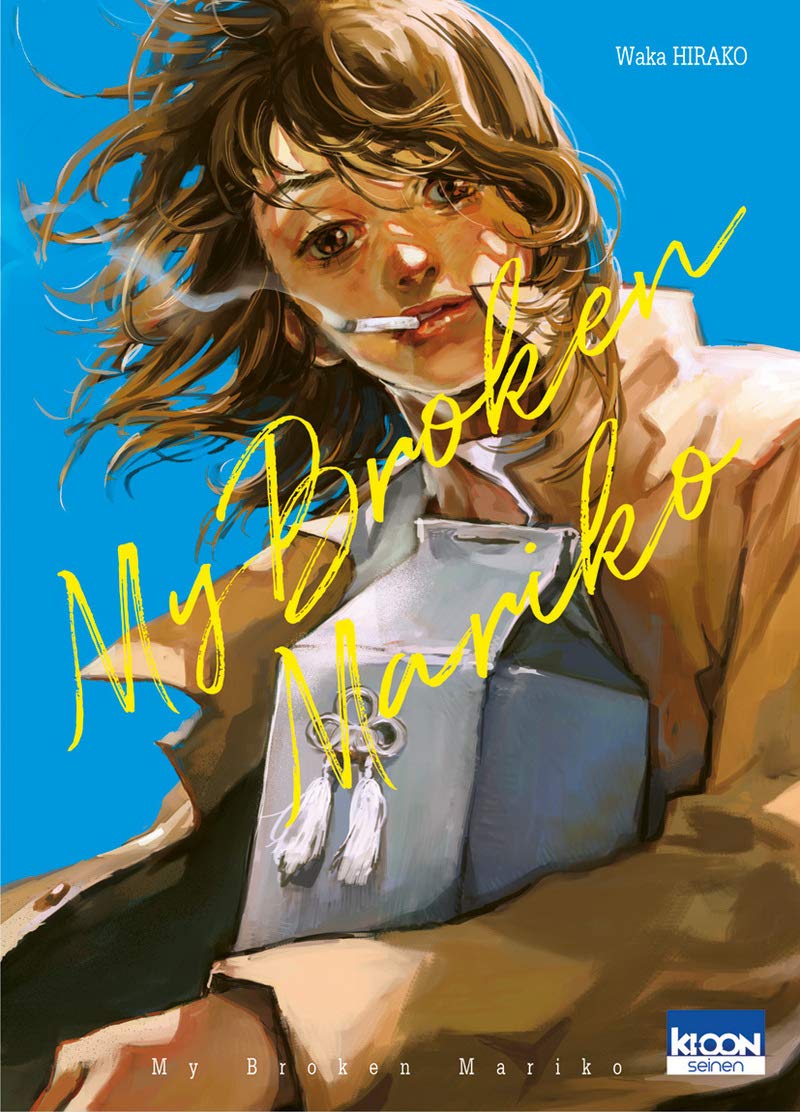

My Broken Mariko is Waka Hirako’s first long manga. It is composed of one volume, and is accompanied by the author’s first work to have been published, the short story Yiska. The mangaka’s engaged work deals with sensitive subjects such as grief, violence towards women, and intrafamilial relationships.

‘I like personal stories that are linked to societal issues’, she explains to her publisher. ‘Starting from the micro to address the macro is, to me, an ideal way to approach a narrative. I think a work always has to have a societal dimension, otherwise it won’t resonate with readers.’

Promoting awareness of violence against women

Waka Hirako’s characters do not conform to the genre stereotypes that are usually the prerogative of seinen manga (for young boys). The heroine in My Broken Mariko, Tomoyo, does not correspond to the conventional notion of femininity at first glance; quite the opposite. She is impulsive, dishevelled, a compulsive smoker, a little lost, and terribly lonely. Her life is far from the commonly accepted ideals of success for women.

Waka Hirako’s pencil strokes also depict a wild character with strained features, who is relatively sombre and emotionally wounded when dealing with grief. These images contrast with the rare moments of sweetness and innocence when Tomoyo recalls the time she spent with her friend when they were young. It is difficult not to be struck by the full-page drawing of Tomoyo as an adult, sitting on a bus, clutching a little Mariko as if in a dream, when reality it is her urn and ashes she is holding close to her heart.

The subject matter of My Broken Mariko does not seek to avenge injustice. It simply reveals that, even in the most critical of situations, it is always possible to retain a sense of humanity. Its release triggered numerous realisations in Japan, where the issue of violence against women, rarely addressed in manga, still waits to be given real political support.

My Broken Mariko (2021), a manga by Waka Hirako, is published by Yen Press.

©Waka Hirako 2020 / KADOKAWA CORPORATION

©Waka Hirako 2020 / KADOKAWA CORPORATION

©Waka Hirako 2020 / KADOKAWA CORPORATION

©Waka Hirako 2020 / KADOKAWA CORPORATION

©Waka Hirako 2020 / KADOKAWA CORPORATION

© Ki-oon, 2021

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.