Katagiri Atsunobu and the Ikebana of Regeneration

A visit to Minamisoma, a town affected by the 2011 disaster, changed the floral artist's relationship with nature and existence.

© Katagiri Atsunobu

To the uninitiated eye, ikebana might look like a simple floral arrangement. In the western world, it might be seen as a passion for bouquets of flowers. However, this discipline goes far beyond the aesthetic dimension, because this art of Chinese origin, which emerged in Japan in around 600 and was initially practised by monks, is also a highly codified philosophical tradition.

Between December 2013 and August 2014, artist Katagiri Atsunobu used a residence in Minamisoma—a small town in Fukushima Prefecture in northern Japan that was struck by the 2011 earthquake and nuclear disaster—to undertake the project The Ikebana of Regeneration. A collection of photographs resulting from this work was later released.

Born in Osaka in 1973, Katagiri Atsunobu became master of the Misasagi Ikebana school at the age of 24. Known for incorporating both traditional and modern approaches in his ikebana work, and for his collaboration with artists from different spheres, Katagiri Atsunobu creates small compositions using wild flowers, and also majestic pieces made from cherry blossoms.

Flowers of renewal

After the region was devastated in 2011, the residents were only allowed to return from 2016 onwards, and discovered a desolate landscape. Although life was yet to resume in the vicinity, the artist tells Pen that he ‘was informed about the regeneration of nature in the area by one of the curators at the Fukushima prefectural museum.’ This search for signs of life in an environment marked by death ‘started out as frequent visits to Minamisoma to create ikebana with the local flowers’, the artist continues, whose work was supported by the Hama-dori, Naka-dori & the Aizu Tri-Regional Culture Collaboration Project. Struck by the devastated landscape and destroyed homes, the artist was also touched by the resurgence of nature, with flowers growing in spite of the situation, amongst the chaos. He started to gather these signs of regeneration of nature and immortalised these arrangements.

The photographs show life, what remains of it, connected with traces of violence, suffering, and death. The flowers are presented among the debris, on carcasses of vehicles, or skulls of animals killed during the disaster.

As Min Byung Jic writes in the text accompanying an exhibition at the Alternative Space LOOP in Seoul, this series is ‘like a sort of ceremony, a performance transcending the simple act of floral arrangement … Relative to human beings’ limited life-spans, flowers are given new life at their last living moments facing death. It is because they blossom again as eternal beauty at the moment of death and life. They possess renewability. For this reason, flowers signify and symbolise renewal and revitalisation.’

When asked about the impact of this experience on how he considers his own existence, Atsunobu Katagiri explains: ‘I think I became more humble to nature. I think I am more keen on the idea of a sustainable cycle of life. I finally purchased a big property in the rural area of Osaka where I live. I am currently planting trees and flowers on that land. My future dream is to be able to create my ikebana work just using things that I grow.’

Sacrifice — The Ikebana of Regeneration (2015), a book of photographs by Katagiri Atsunobu, is published by Seigensha.

© Katagiri Atsunobu

© Katagiri Atsunobu

© Katagiri Atsunobu

© Katagiri Atsunobu

© Katagiri Atsunobu

© Katagiri Atsunobu

TRENDING

-

A House from the Taisho Era Reveals Its Secrets

While visiting an abandoned building, Hamish Campbell discovered photographs the owner had taken of the place in the 1920s.

-

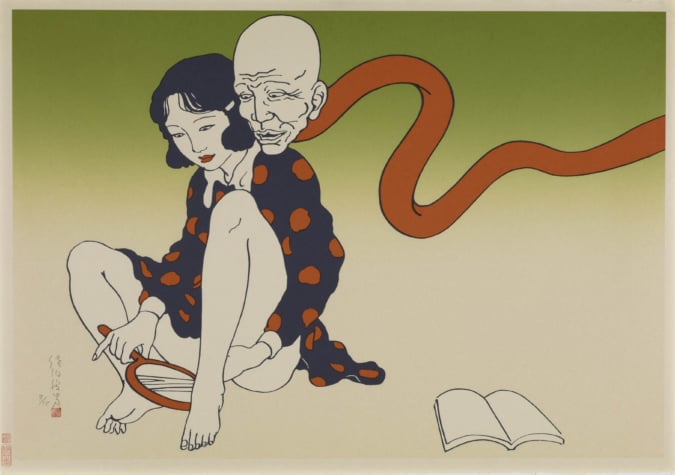

The Taboo-Breaking Erotica of Toshio Saeki

The master of the 1970s Japanese avant-garde reimagined his most iconic artworks for a limited box set with silkscreen artist Fumie Taniyama.

-

With Meisa Fujishiro, Tokyo's Nudes Stand Tall

In the series 'Sketches of Tokyo', the photographer revisits the genre by bringing it face to face with the capital's architecture.

-

Masahisa Fukase's Family Portraits

In his series ‘Family’, the photographer compiles surprising photos in which he questions death, the inescapable.

-

Hajime Sorayama's Futuristic Eroticism

The illustrator is the pioneer for a form of hyperrealism that combines sensuality and technology and depicts sexualised robots.